What makes things erotic? An exhibition in the Museum of Things, Berlin, presents a wide range of objects with an erotic dimension – some intentionally, others due to our vivid imagination. Continue reading “Erotic Things”

Tag: scenography

Private Photography

The exhibition FOTO | ALBUM in the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge, Berlin shows private and anonymous photography from the vast collection of the museum. Do not miss it – it is great fun and runs till February 26th, 2018. Poster and exhibition graphics by Rose Apple. Continue reading “Private Photography”

Cabinet of the Unknown

The Werkbundarchiv – Museum of Things and guest curator Ece Pazarbaşı invited its neighbours to select “unknown” objects in their vast collection and collectively assemble this exhibition of 65 enigmatic things. They serve as talking points to participants and visitors alike, with the aim to collectively generate a pool of knowledge that goes beyond the conventional museum wisdom. Come and share your knowledge as well until September 25, 2017. Continue reading “Cabinet of the Unknown”

Would You Like It Modern?

The exhibition gern modern? Living concepts for Berlin after 1945 at the Museum der Dinge charted ideas and initiatives of the German Werkbund in the aftermath of WWII.

Chapel for 30 Seconds

What are you afraid of? You had 30 seconds to ponder this existential question, while crossing the light tunnel over river Ill. The installation by Alex Valder and myself in picturesque Feldkirch was part of the Montforter Zwischentöne, an innovative music festival. The theme of that year’s edition was “Faith”.

Photo: Elias Keimer

The questions mounted at either end of the bridge were changed every day to entertain regular users of the bridge as well as the one-time visitor from out of town. The closer you got to the questions, the less legible the letters became.

The bridge connects the town and the Montforthaus – the festival’s base – with the music academy on the other side of the river, which served as a venue for some festival acts.

Photo: Elias Keimer

In the early November nights the illuminated bridge showed visitors the way and signalled to the population that the festival was ‘on’.

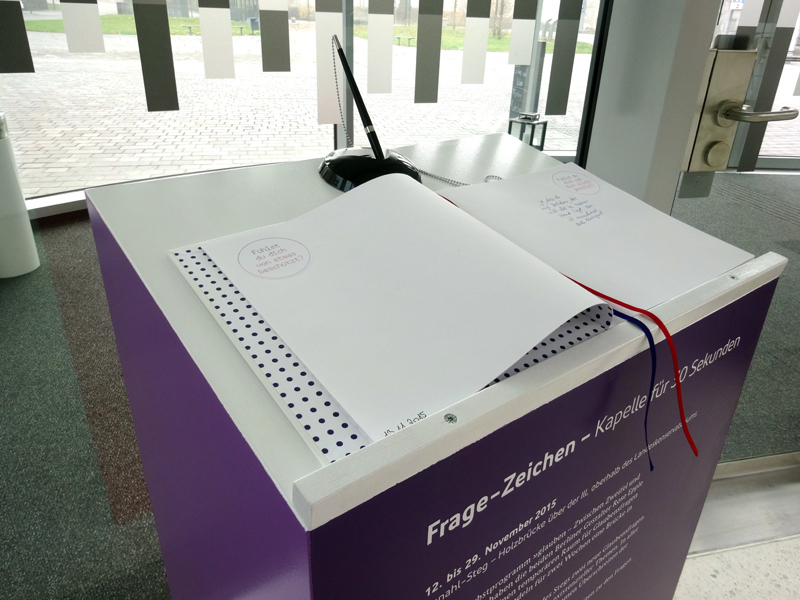

A visitors book in the Montforthaus invited you to share your answers, reflections or comments to the question of the day.

Frage-Zeichen. Kapelle für 30 Sekunden, an installation by Rose Epple and Alex Valder with the help of lighting expert Elias Keimer for the Montforter Zwischentöne from November 12-29, 2015. The festival is curated by Hans-Joachim Gögl and Folkert Uhde.

Title image © Darko Todorovic

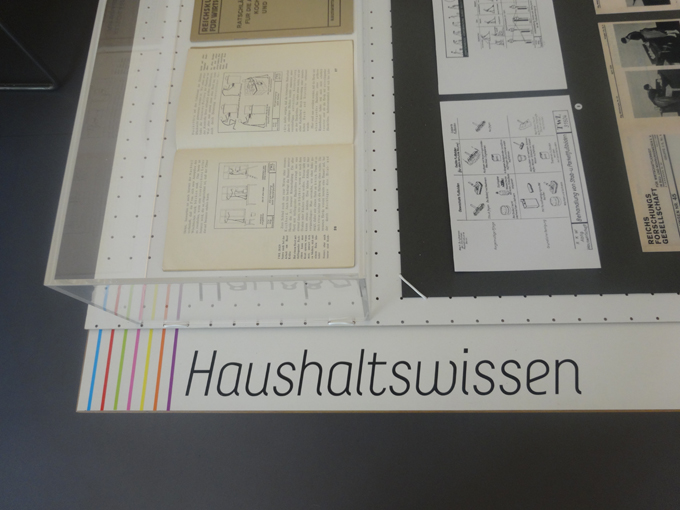

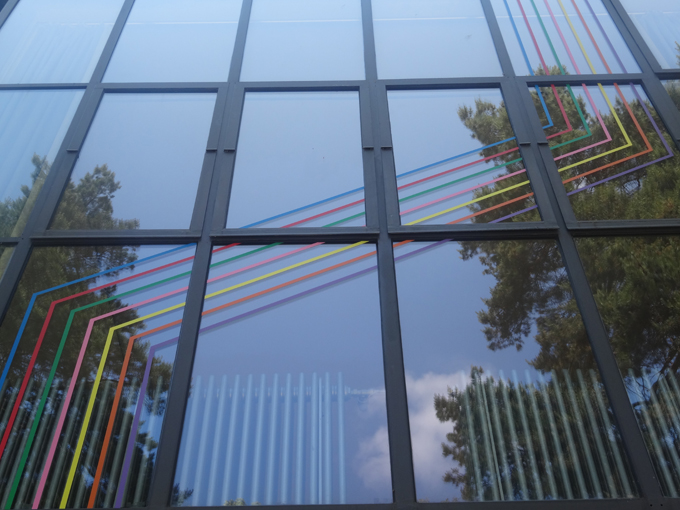

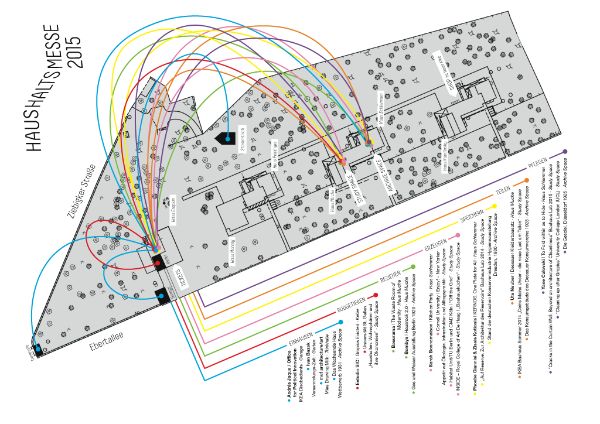

Haushaltsmesse 2015

The masters’ houses in Dessau – built by Walter Gropius for the Bauhaus Masters in 1926 – were used as object lessons to promote Bauhaus ideas of modern living and household management. For the ‘Household Fair 2015‘ of the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation they serve as a point of departure for the investigation of contemporary housekeeping and budgeting issues. The fair comprises historic material as well as contemporary artistic positions and research on the household as a modus operandi ranging from the individual house to the entire world.

It was my pleasure to design the visual identity, signage and exhibition graphics for the Haushaltsmesse 2015.

Haushaltsmesse 2015. The art of housekeeping and budgeting in the 21st century | A project of the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation in the masters´ houses from June 12 to August 9, 2015 | curators: Regina Bittner, Elke Krasny | project management: Katja Szymczak | design: Rose Apple with Wolfgang Schneider | For more information on the project click here.

All photos by Rose Epple unless otherwise indicated

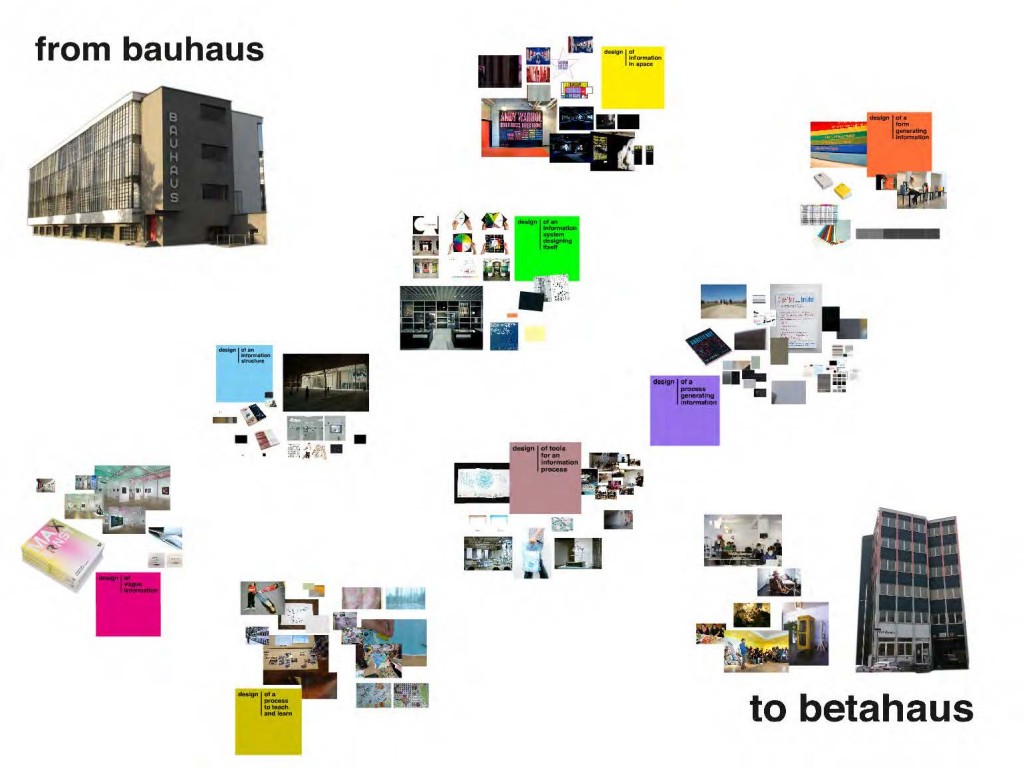

From Bauhaus to Betahaus

My recent lecture for Shapeshifters in Brussels, provided me with a good excuse to look at my work from the last decade and try to make sense of it all. Am I still the same designer as ten years ago? No, I have changed and so has the design world around me. Roughly, I would sum up this change as a move from form to process.

Since 2003, Johan van Looveren and Inge Gobert from Sint Lukas Hogeschule in Brussels, have invited graphic designers for their annual lectures to talk about their approach to information design. When they asked me, it was the first time I thought about my scenographic work and book projects as information design. Have I been designing information? If so, where did this information come from, what did I do to it and why? To answer these questions I had to go right back to the Bauhaus, because for me it all started with the Bauhaus.

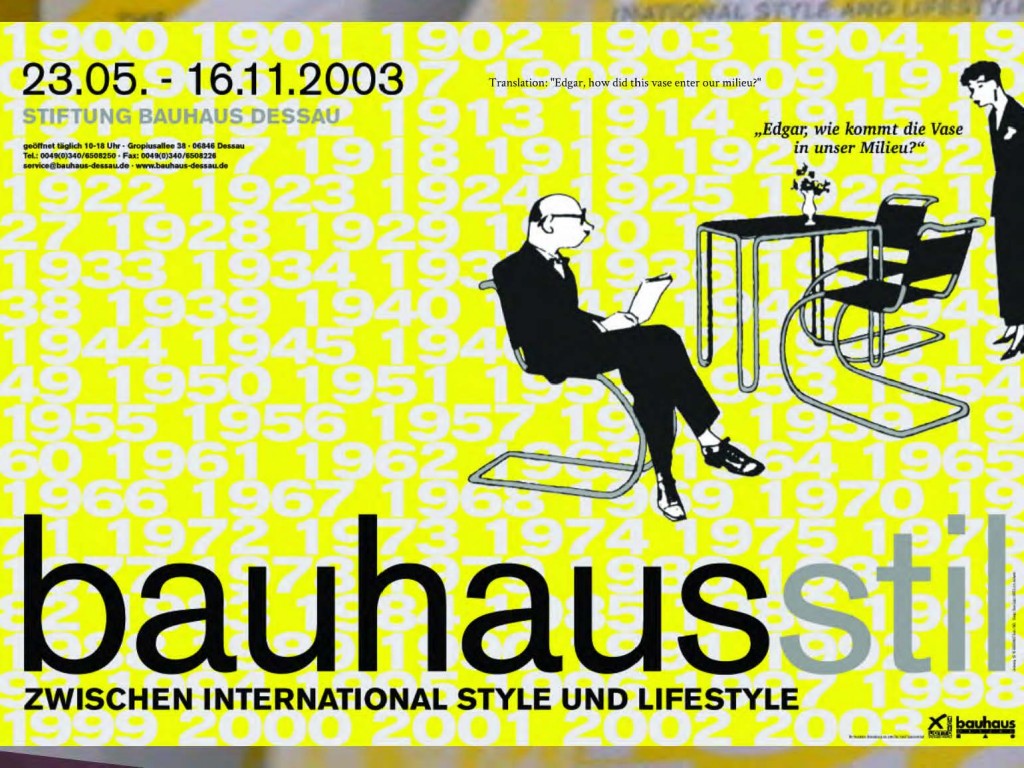

One of the first exhibitions I ever worked on was Bauhaus Style at the famous building in Dessau. By the time this opportunity arose, I had already come a long way. Originally starting off as an illustrator, I was quickly frustrated by the limited scope of a typical commission: “Your drawing here, please.”. What about the rest of the page? What about the article, the magazine, the series, the brand? My constant urge to design an ever bigger context was finally matched by the design brief: create an environment. In an exhibition the things that are exhibited plus the exhibition design embedding them into a context, constitute together what you might call “the information”. It is transmitted over a range of different channels simultaneously. To design these parallel levels, you obviously need more than one design discipline. The idea that all design disciplines work together towards one vision, their “cathedral”, was first propagated and put into action at the bauhaus. One could say, that scenography or integrated design itself started with the bauhaus.

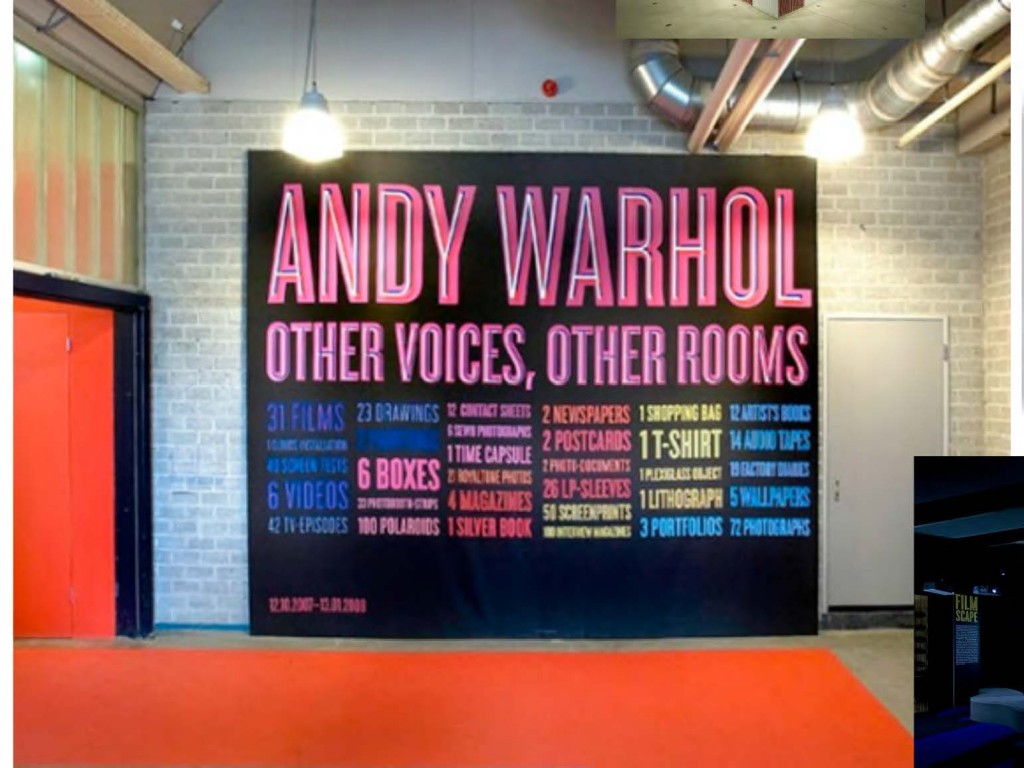

An exhibition is not a linear 3-D book that you read from A-Z in order to learn something. In the exhibition Andy Warhol. Other Voices, Other Rooms that originated in the Stedelijk Museum and travelled from there to Stockholm, London and Columbus/Ohio, that would have been an impossible undertaking anyway. In the spirit of “All is pretty” (Andy Warhol) the show combined 871 works in 33 media. In order to view all time based media alone, it would take a visitor close to 68 hours.

An exhibition is a world that you enter, and you experience information rather than reading it. A narrative space can convey meaning in a more direct and sensual way than a book. The defining difference seems to me the physical presence of the visitor and his movements around the space.

Information gets altered not only by what is exhibited and how, but also by the way the visitor moves around the space, the time she spends there and the way she feels while being there. Thus, the design of an exhibition is not comparable to designing a static object or a theatre stage, but is more akin to city planning or service design.

This is why information in exhibitions is context sensitive. Let´s take for example the filmscape in the same exhibition where 21 films run simultaneously in a sound absorbing camouflage landscape. The arrangement allows for a comparative filmic experience, very appropriate for Warhol´s highly experimental films, that range from short camp movies to nine hours footage of the Empire State building filmed in one night.

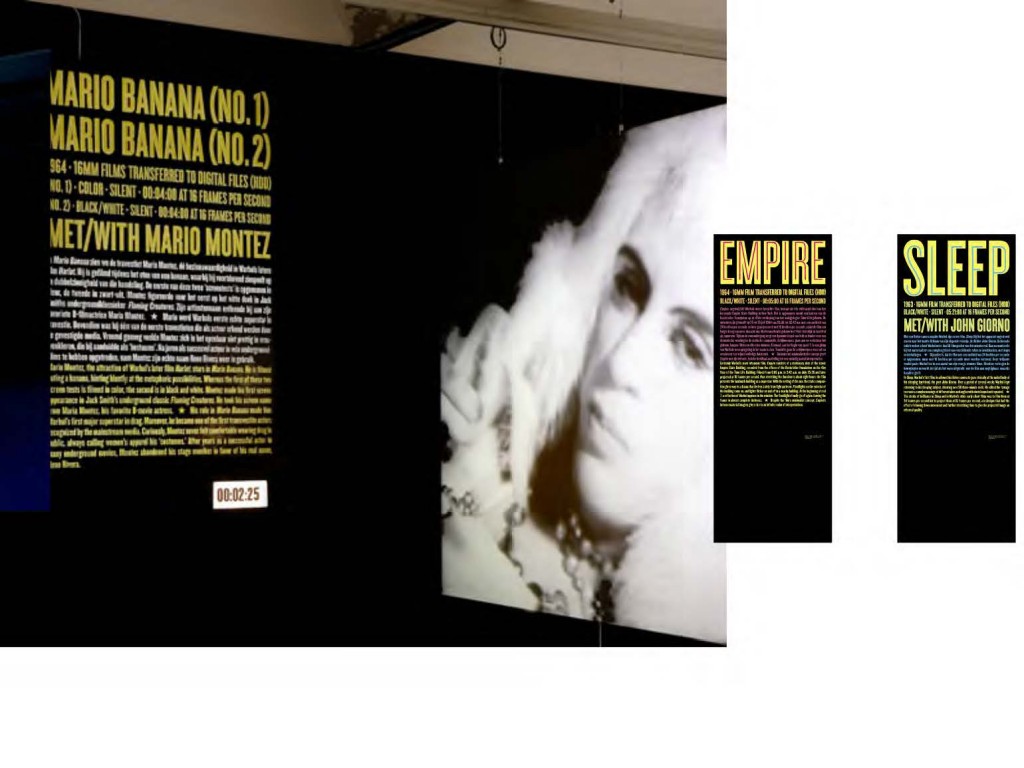

The physical sensation of walking and lying around in films is impressive enough, but an interested visitor might like to know what exactly he´s watching. This is usually solved by sticking a label somewhere, but here it is dark and you wouldn´t be able to read a normal label in the dark. That´s why we enlarged the information on each film and put it on those big panels on the walls. These panels show you title, actors and duration of each film. But one problem, that people usually have with time based media in exhibitions remains: how do you know at what point the film is right now? To solve this problem, we incorporated a timecode into each panel, showing you the exact position of the film.

A different situation in the TV scape, which displays all 42 TV Shows by Andy Warhol on individual screens. Here the star seats hold the information. The visitor is literally sitting on the information, as only one person can watch one show at one given moment. People have to move around the room to view a different episode, they are switching channels with their bodies. The way information is presented makes them do that. Seen from the outside, the visitor almost becomes an exhibit in himself, luring other visitors inside the American Flag thus completing the exhibition design.

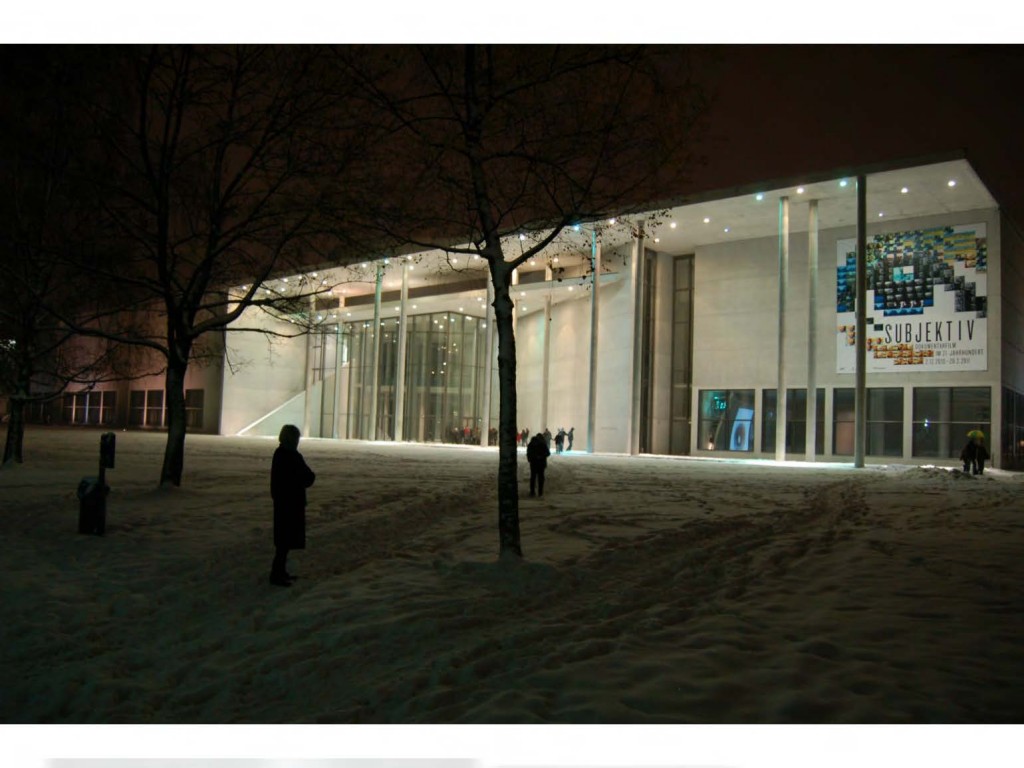

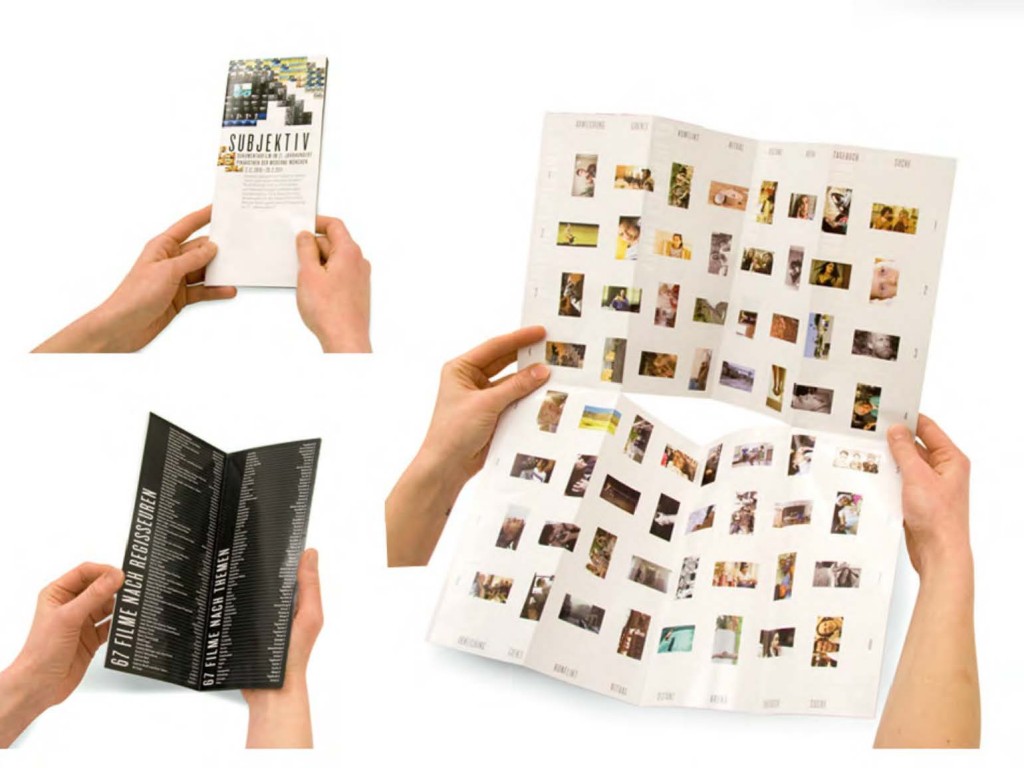

To give a visitor information he needs at a specific moment is one strategy, another is to provide him with a tool that enables him to navigate independently around complex information environments. The exhibition Subjective aimed to portray a generation of documentary filmmakers from the Film and TV school in Munich in the neighbouring Pinakothek der Moderne, allowing for an interdisciplinary exchange on the nature of the documentary in art and filmmaking.

The advantage of doing this in an exhibition as opposed to a film festival or a DVD set, is the possibility to let visitors see everything at once. The overview took place in the main exhibition room, where 88 documentary films were simultaneously shown, each film on its own white museum style socle. Projected by a mini beamer, the size of a pack of cigarettes, unto small plexi screens, each film thus had its own tiny cinema situation to itself.

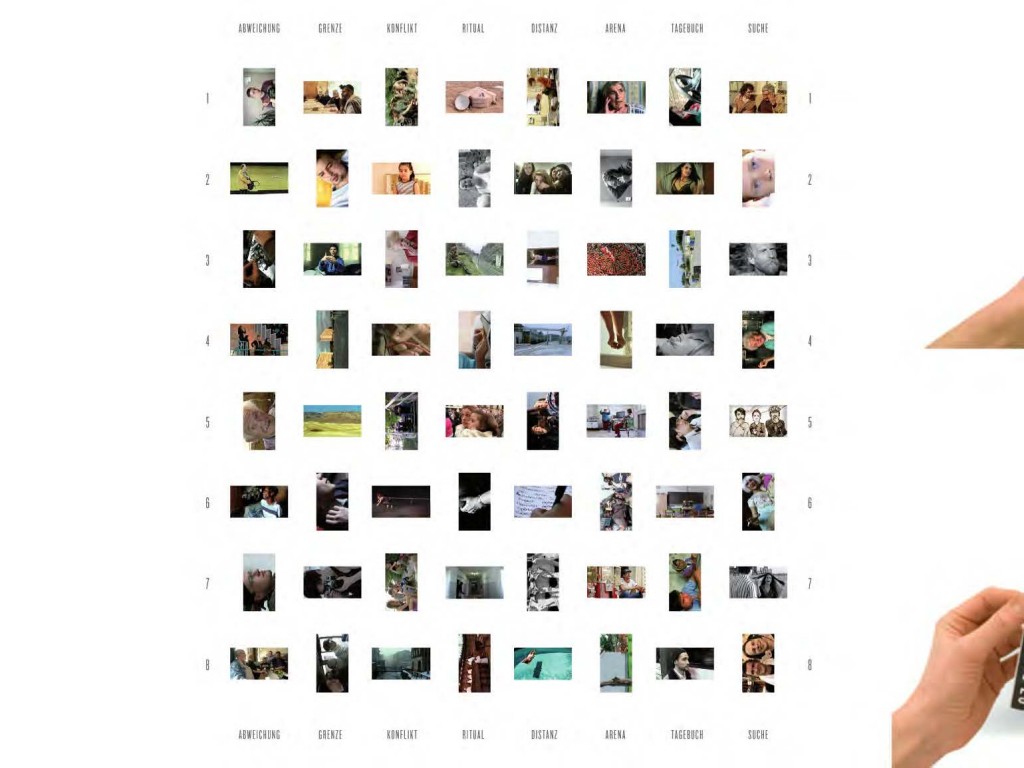

The visual floorplan shows the rigid grid on which the films were arranged. Vertically you have a number system, horizontally each row represents a curatorial group with titles like “conflict”, “border” e.t.c.. In the accompanying fold out map, the visitor can search for films by different categories, such as director, film title or subject matter. Just like on a city map, the visitor is given the coordinates of the particular film, he has thus chosen.

For younger people that were raised on the internet, the navigation of complex information and being offered alternative routes for personal explorations, seems natural. For the designer, the main feat is a usability challenge. How do you design an easy to grasp system that allows people to explore on their own? But this scenographic approach also has a wider impact, it subverts the hierarchical roles of curator and visitor, of expert and laymen to allow for a more democratic interaction between equals.

But there are different types of information. There is the type of information that spells “This way to the toilet” or “Max Ernst was born in 1891”. But what about how his works feel or what it means? In the comprehensive Max Ernst retrospective Max Ernst. Dream and Revolution at the Moderna Museet and the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, the curators wanted to show that Max Ernst influence on contemporary aesthetics and thoughts, is much greater than commonly acknowledged. How can you make people get a glimpse of these curatorial ideas, beyond using textual means? How can somebody that only walks through an exhibition without reading a single label or text experience Max Ernst as a contemporary, not just as an exponent of the historic surrealist movement?

To give the exhibition a contemporary feel, without scaring off the rather conservative (when it comes to exhibition scenography) art crowd, we worked exclusively with museum means: white walls and lighting. The freestanding walls form different types of rooms, connecting and structuring the works loosely, while coloured lights aimed at the ceiling indicate the four sections of the exhibition. Each colour represents one of the four different places where Max Ernst lived and worked: the early Dada works in Germany are signalled by green light, his French works hang under a pink sky, the American ones in a yellow aura and his return to Europe in the fifties glows blue. The labels emanate the same coded colours, achieved by simply sticking coloured paper on the back of the labels and attaching them in a little distance to the wall.

Even the catalogue emits coloured light from the spine, subtly illuminating the different sections. Vague information needs artistic rather than rational means.

So far the information as subtle as it may have been, has had a reliable source. It was usually provided by curators, which are experts in their particular fields. But increasingly, the roles of information provider and information consumer in my projects have become more fluid.

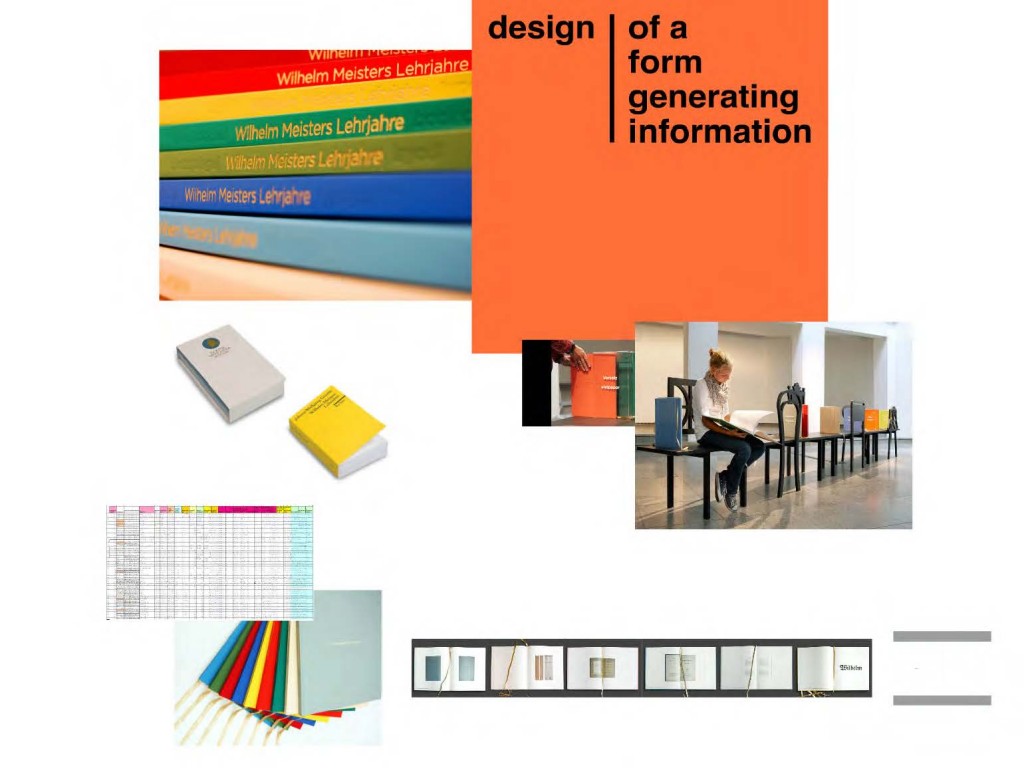

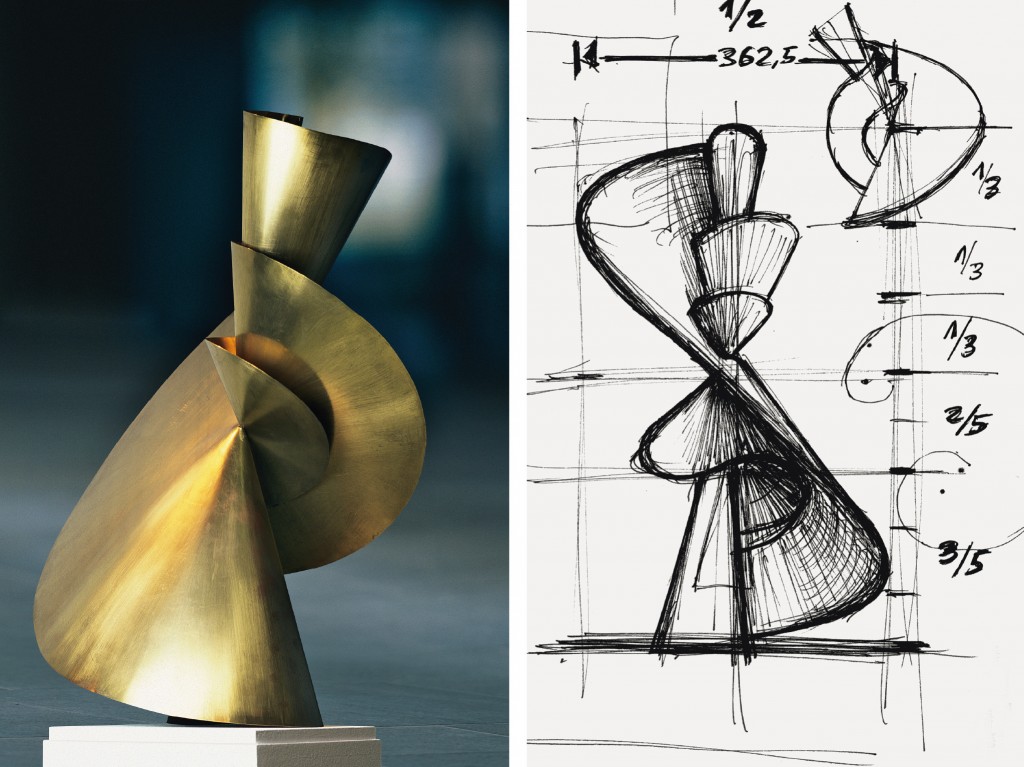

Examples are the Wilhelm Meister exhibition, where new knowledge was generated by the scenographic form. The exhibition books make information visible, that has not been visible before, even to the experts. They show aspects of the Goethe Book, which go beyond the usual literary objects of study and provide new entry points to the book, even to people that are not familiar with the text.

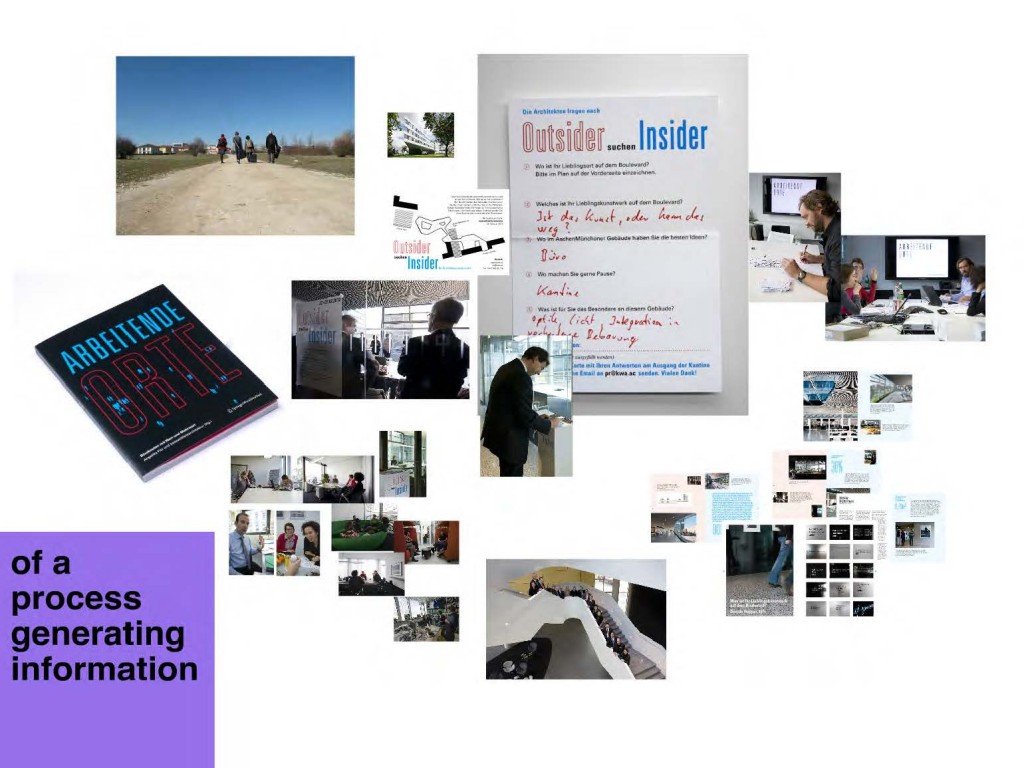

Or take the book project Arbeitende Orte (transl. Working Places) with Angelika Fitz, where we first designed a process, in order to collect the information that would subsequently form the content of the book.

Another exemplary project might be the planned International Building Exhibition IBA Berlin 2020, for which we designed the first public interface in the ongoing process. To enable this process, we designed artefacts that were not ends in themselves, but means to an end, such as the flexible and modular IBA Workshop platform and simple tools such as pens, sticky notes and plastic bags (to carry information away with). In the temporary IBA Workshop in the airport Tempelhof, new information was jointly generated, information that is then being fed back into the process to spark off new ideas and so on and so on.

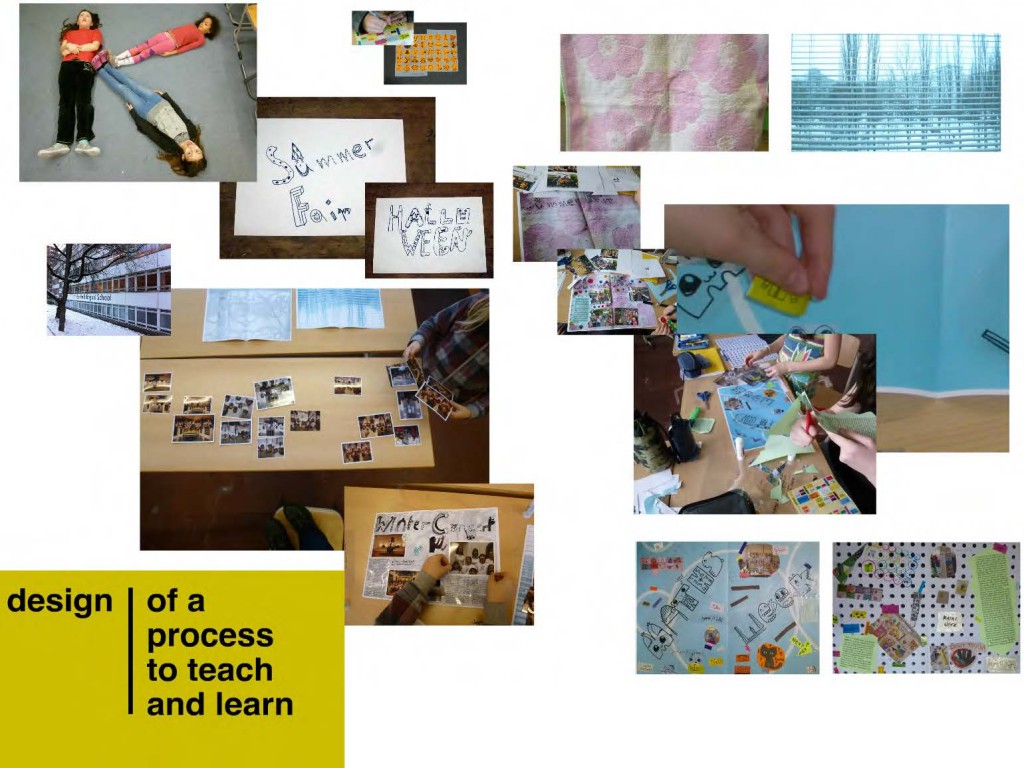

I would like to close this list of information frenzy, with the yearbook project where I am designing a book with school children. To enable them to do this I am designing a process to inform and end up learning as much as I am teaching. To find out more about this lively experience please refer to Co-designing a Yearbook.

Having come full circle and finding myself back in the present, I can claim that looking at my work from an information angle proved fruitful. The filter allowed me to see more clearly how parameters, objectives and outcomes have changed and shaped my design perspective over the years. Not only the way information is created, handled and offered has changed in my projects, but also my working conditions as a designer. My latest endeavors all share some characteristics: fuzzy timespans with no clear start and finish, a collaborative process that has to be constantly adapted to meet its objectives and an evolving definition of the desired end result, a result that often triggers more questions rather than give definite answers.

I am not alone. All around me I see designers moving from commissions to questions. I see people reinventing our profession, working in changing constellations on self professed beta versions. Which brings me to the other haus that starts with a small b and to the end of my musings.

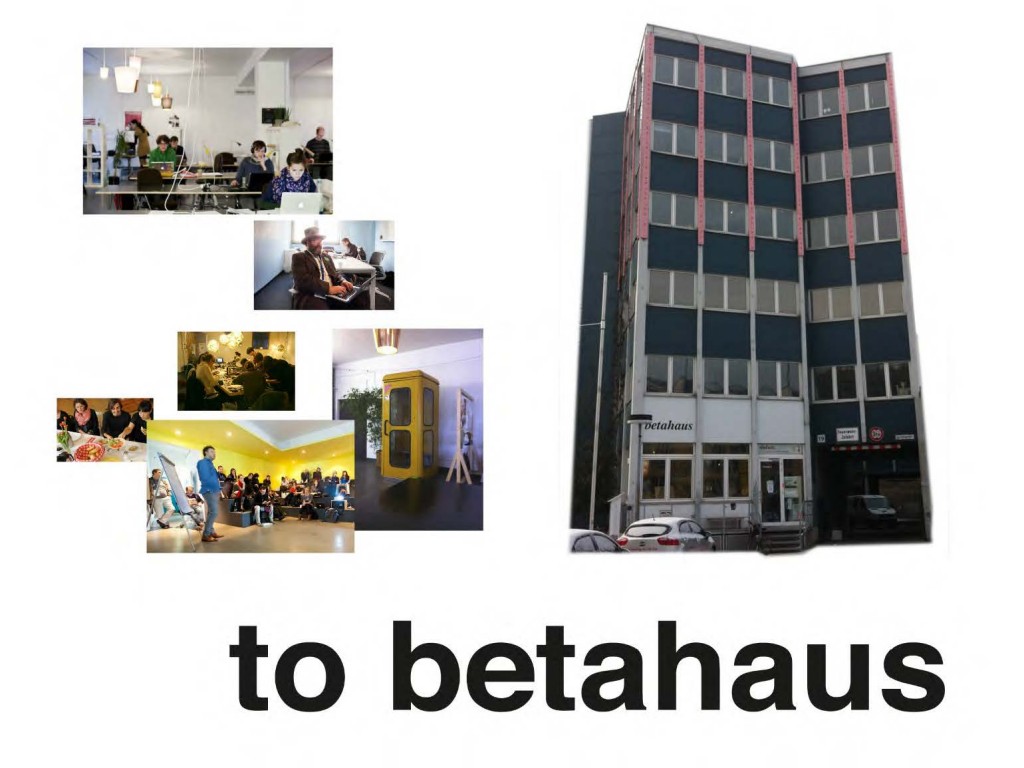

The betahaus is a co-working space in Kreuzberg that rents out desk space to people like me – people that don´t like to work alone at home. Just like the Bauhaus almost a hundred years ago, it is a platform that encourages people from different disciplines to meet and work together on projects. It uses tools like weekly breakfasts, open office hours and maker weekends to facilitate exchange and create synergies. Like the famous school it is as well a place of learning.

But unlike the historic Bauhaus, you don´t have to master the “Grundkurs” first. The betahaus is open to everyone and the roles of teachers and students in the betahaus are interchangeable: one day somebody will show you how to create interactive textiles, the next day you can teach them screen printing or send your kids to a hackathon. The betahaus exports its concept to other cities and countries, creating an “international style” of co-working that is designed to be shaped and defined by its users. The “beta” in the name is programmatic, the betahaus sees itself as an institution in flux, a dynamic prototype where ideas are tested, refined or thrown out again.

The betahaus seems to me very much a child of its time – just like me.

Andy Warhol. Other Voices, Other Rooms, Subjektiv. Documentary Film in the 21st century, Max Ernst. Dream and Revolution, Wilhelm Meister exhibition, IBA Berlin 2020: scenography by chezweitz&roseapple · Wilhelm Meister Bücherkörper curated by Rose Epple

Talk for Shapeshifters on March 13, 2013 at Beursschouwburg, Brussels.

Discover the Void

Some people thought it was a mistake when they received the empty envelope. They called up the sender, the city of Halberstadt, to be told that this envelope was indeed their invitiation to the opening of “Discover the vo d”. The callers had interpreted the void as the absence of something and they wanted to fill that empty envelope, just as one automatically fills in the missing letters of the exhibition title. The invitation had triggered the mental process which the exhibition was exploring.

People in Halberstadt, a small town in the picturesque Harz region in Eastern Germany are experienced void fillers. A woman, who was only a baby on April 8, 1945, when allied bombers destroyed 82% percent of the medieval inner city, told me that she was raised on tales of this invisible city of the past. Wandering around the ruins, relatives would recount to her every lost building, street corner, flagstone. She grew up with a very clear picture of houses and streets that didn´t exist anymore and she shared this vision with the people around her. Even today, the dials of the big clock on the tower of Martini Church are permanently stuck at 11.28 a.m., the moment desaster struck 67 years ago.

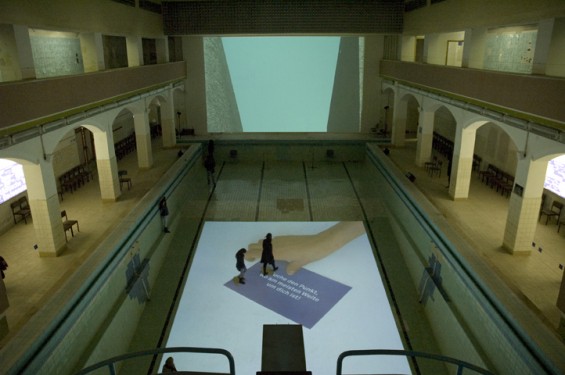

To get Halberstadt unstuck from viewing emptiness in their city solely as a traumatic loss was the focus of the International Building Exhibition (IBA) Urban Redevolpment Saxony-Anhalt. An amibitous IBA team made up of members of the city council, town planners, architects, cultural scientists and a scenographer (my former business partner Detlef Weitz) set out to cultivate alternative attitudes towards empty spaces. In a long process involving many different local individuals and groups, they identified and analysed different forms of emptiness and explored mulitple uses of empty space in the town. They succeeded in not filling the empty spaces with buildings, but with new meaning.

When we were commissioned to present the results of this process in a final exhibition in the derelict municipal swimming baths, we not only wanted to show the visitor what had happened during the IBA years. Our aim was to show emptiness itself. Thus, we projected a walk-in videoinstallation unto the floor of the empty swimming pool, just like the people had projected their lost city unto the empty spaces of the destroyed city.

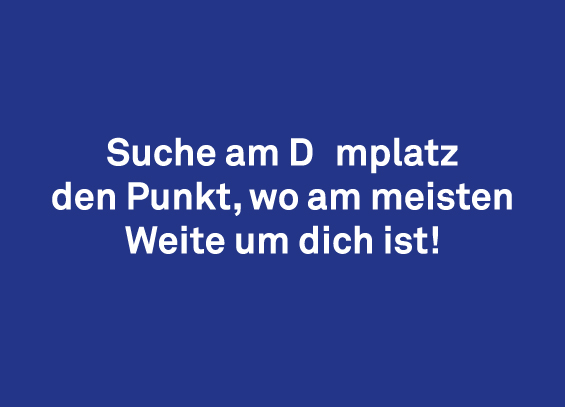

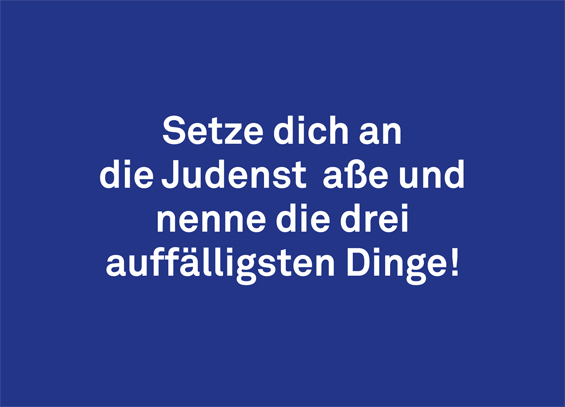

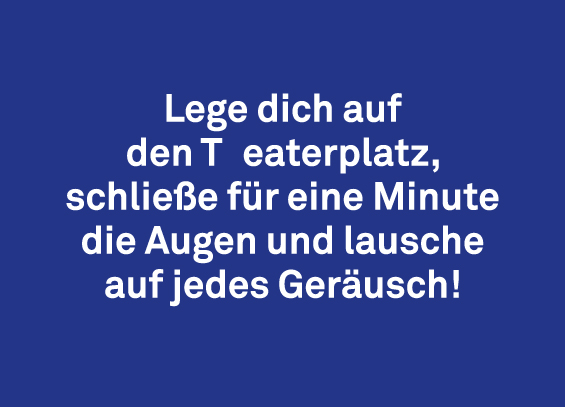

Giving something as abstract as empty space a form, is one way of communicating it, to invite people to experience emptiness for themselves is another. On postcards that could be collected in the exhibition, visitors were asked to visit “empty” places in Halberstadt and go through a series of simple exercises to help them feel emptiness for themselves. Please feel free to adapt these exercises to your personal surroundings and let us know how it felt.

Scenography by chezweitz & roseapple

Photos by Volker Kreidler

Scenographic Field Studies

Brief: Find the most auratic object in the museum and make a sketch of the way it is presented.

Indeed – there seems to be a consensus among students in choosing the Nofretete as the most auratic object in the New Museum Berlin, which I count as proof that something of that kind of phenomena exists. Although I personally still have my doubts…maybe the testgroup was still too small?

The seventeen students of the Technical University’s Master in Stage design and spatial composition produced these drawings as part of the data collected in three scenographic excursions. Franziska Ritter, the course coordinator, and myself devised these field trips in order to raise awareness for the different levels scenography is acting on and also because we were curious if this combination of research and education would work.

For the first trip we set out to compare two very different exhibitons about the Berlin Wall. One being the newly opened Berlin Wall Memorial along Bernauer Straße and the other the Mauermuseum Checkpoint Charlie. Each researcher had a different task on hand: counting and categorizing exhibits, following people and timing them looking at exhibits, measuring text lengths, testing orientation and navigation, listening with their eyes closed, collecting soundbites, smelling and touching the exhibition, observing their emotional reactions to the exhibits, sketching floorplans and mapping the curatorial structure. In the following round up these findings were presented and combined to a comparative study, obviously with no real scientific credibility, but packed with surprising observations that made the ensuing discussion very lively.

Would you have guessed that people spend less than one minute in front of an exhibit and maximum three minutes in a whole section? That original audio recordings score very high on the emotional scale? That a hard floor covering creates an aggressive noise and that small stuffy rooms produce smelly people? Another astonishing miscellany being that the Mauermuseum has the highest number of visitors in Berlin, although it scored very badly in the study. One student called it “a giant newspaper”, a tabloid rather, and everybody was very confused about the curatorial structure. Still, if you´ve never been there I can highly recommend it as a memorable experience – it has an endearing naiveté about it, you could say a museum brut.

On the second trip we focused on the object, comparing the display of and the attitude towards the objects displayed in the New Museum Berlin and the Museum of Things respectively. The former houses the Nofrete and yes, there is an auratic object in the latter as well. Go and visit or buy the new Lou Reed CD and you‘ll see. Again, it was so productive to work with a whole research team. Fourteens brains observing simultaenously produce indeed more data, more complexity, more controversy and more insights for everybody.

All drawings by MA students of the TU Stage Design and Spatial Composition course

Inter Versus Multi

Scenography is per se an area where a multitude of disciplines come to work together. In order to create a compelling exhibition experience for the visitor you have to consider space, movement, objects, words, orientation, surface, light, sound, emotions, products and the translation of physical space into printed matter and digital space. Which means that you need architects, product designers, writers, programmers, light and sound specialists and of course graphic designers, those who are good at working in real space and those who understand the intricacies of book and web design. And this list is only on the design side of things.

Rereading ‘Change by Design’ by Tim Brown, an advocate of design thinking, I stumbled across an interesting definition of the nature of team work across disciplines. “In a multidisciplinary team each individual becomes an advocate for his or her own technical speciality and the project becomes a protracted negotiation among them, likely resulting in a gray compromise. In an interdisciplinary team there is collective ownership of ideas and everybody takes responsibility for them.”

From my experience a scenographic design team often starts out as an enthusiastic inter in the ideation phase, veers into an edgy multi in the execution phase only to come together again on the home stretch to celebrate an ecstatic inter success at the opening.

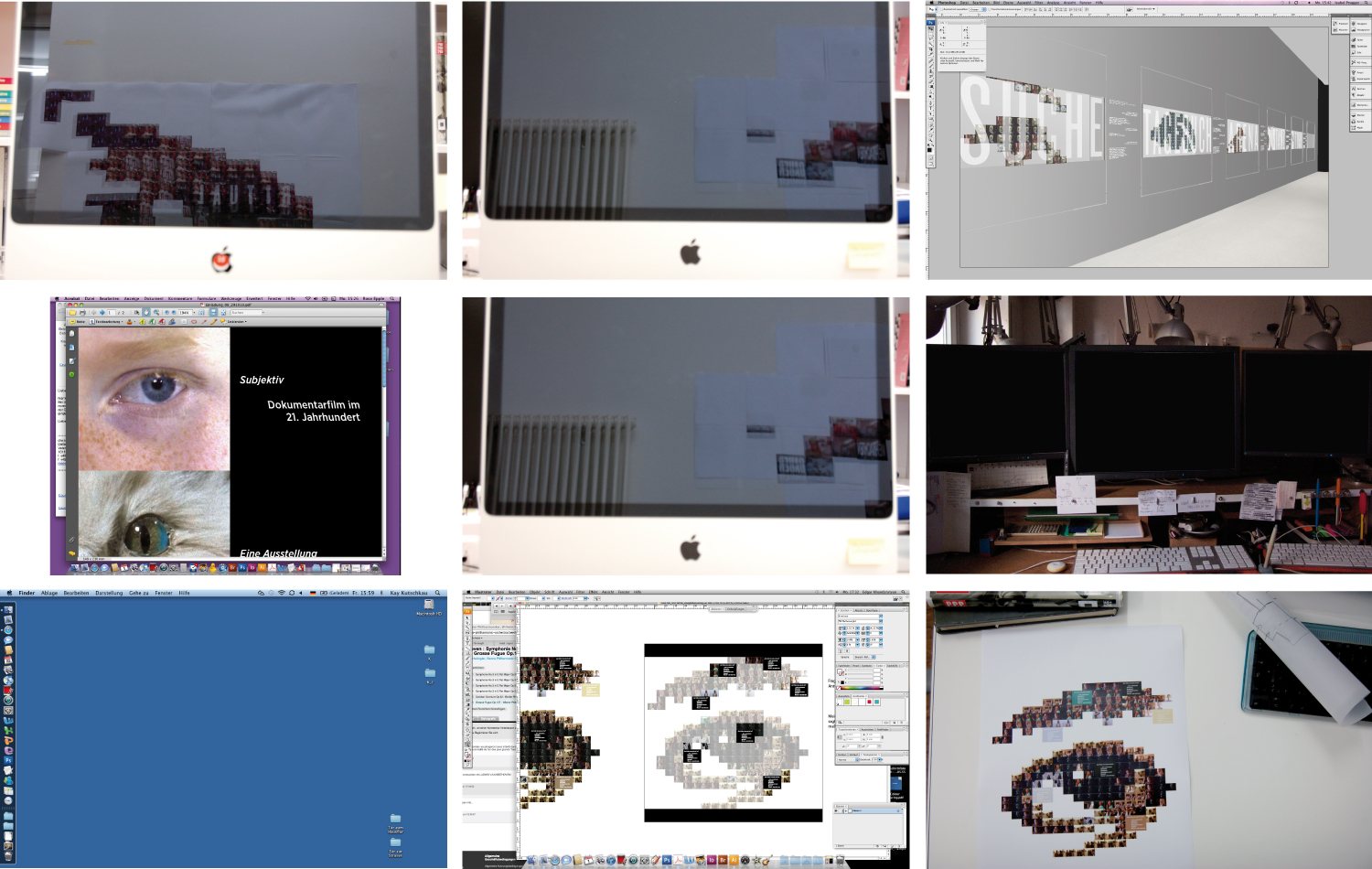

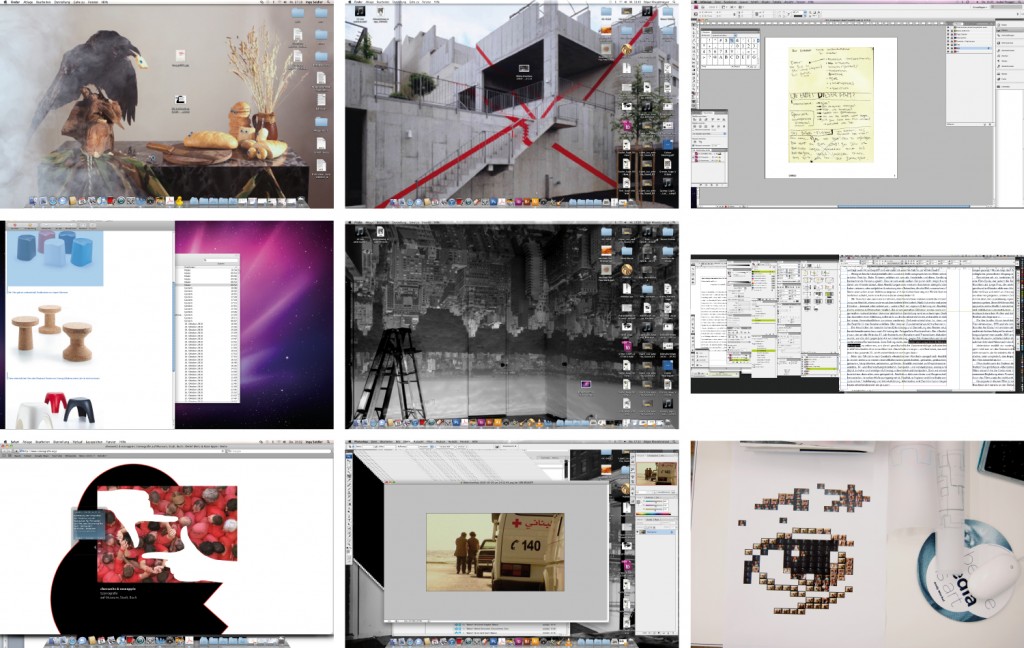

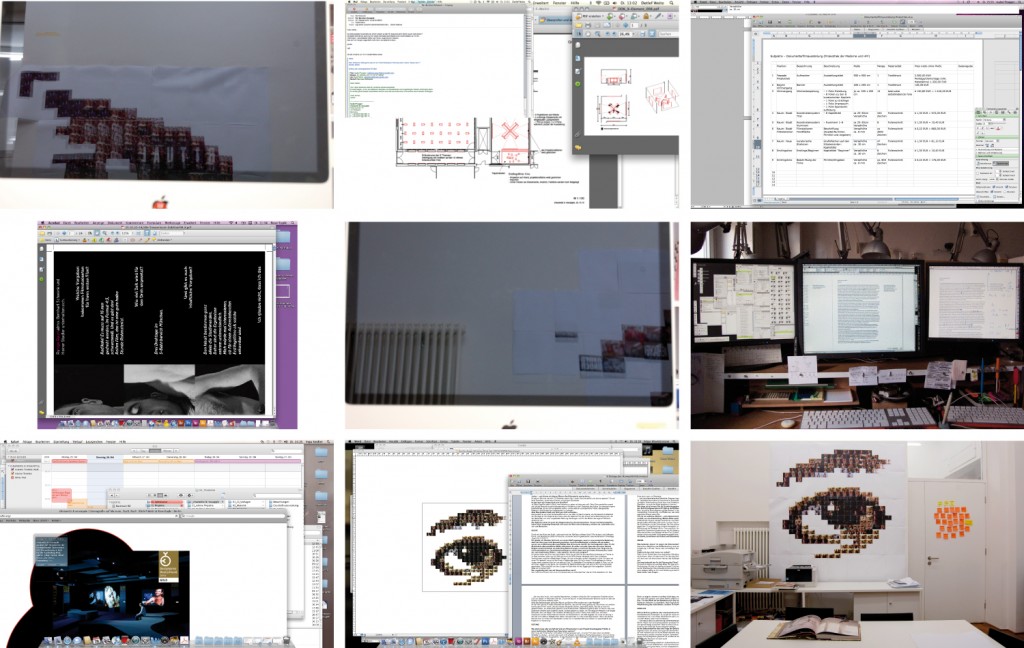

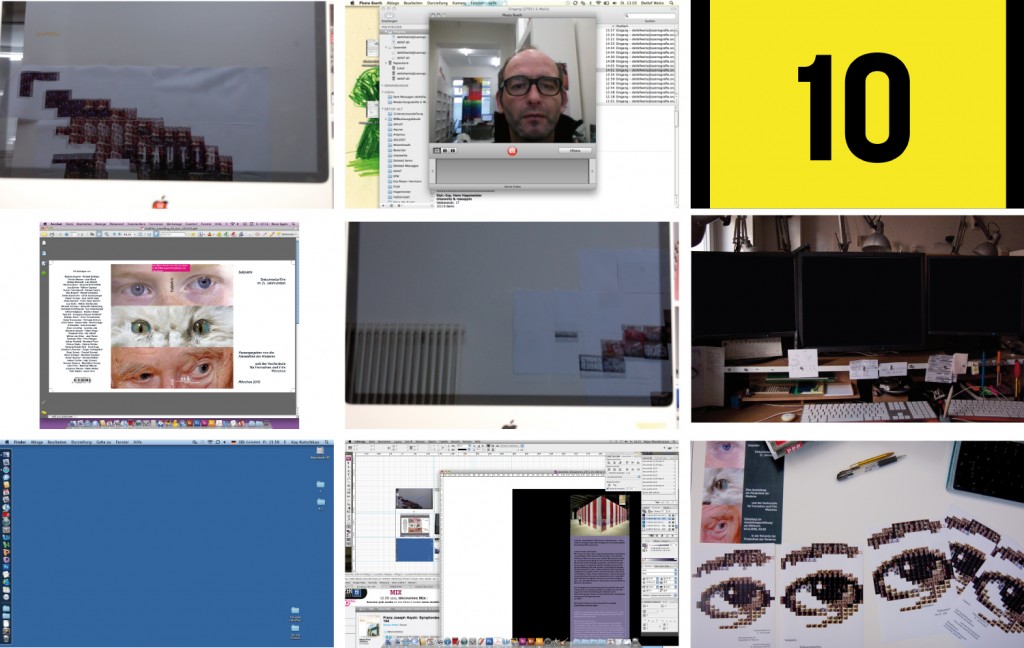

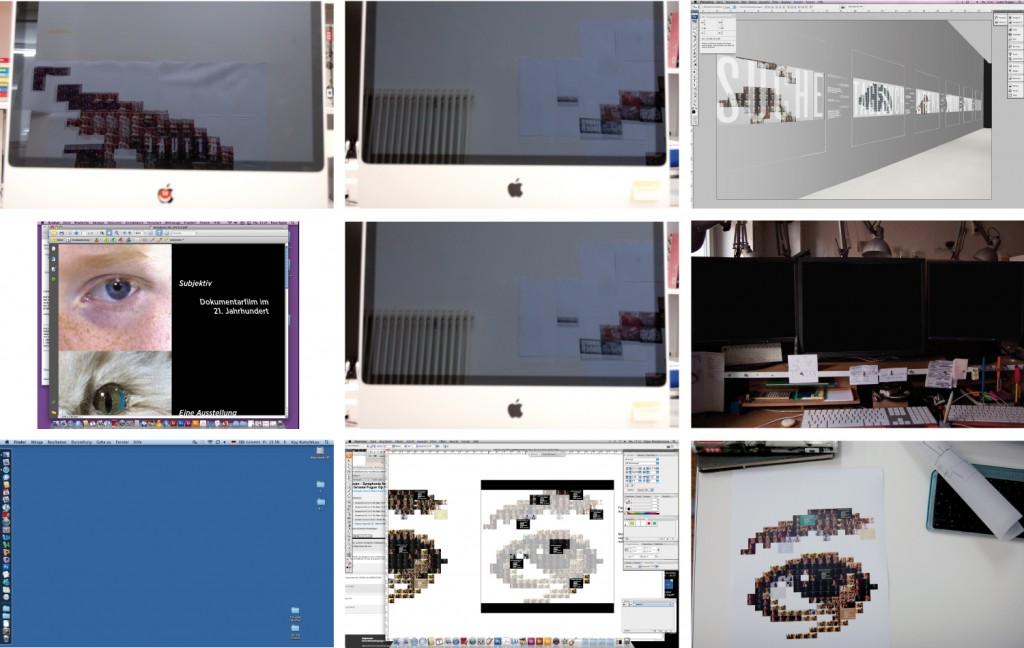

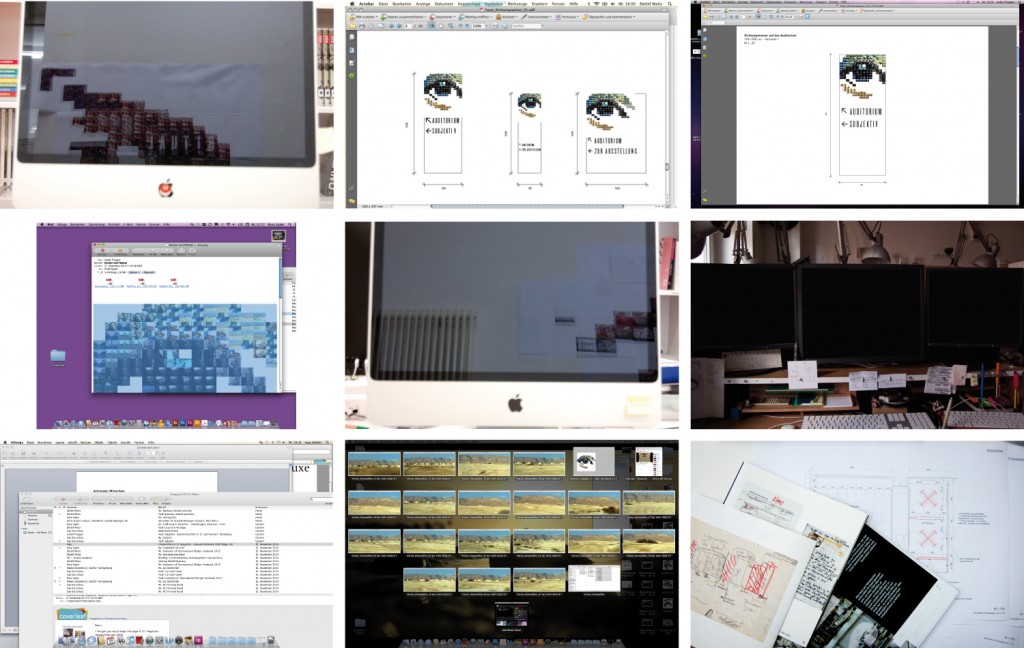

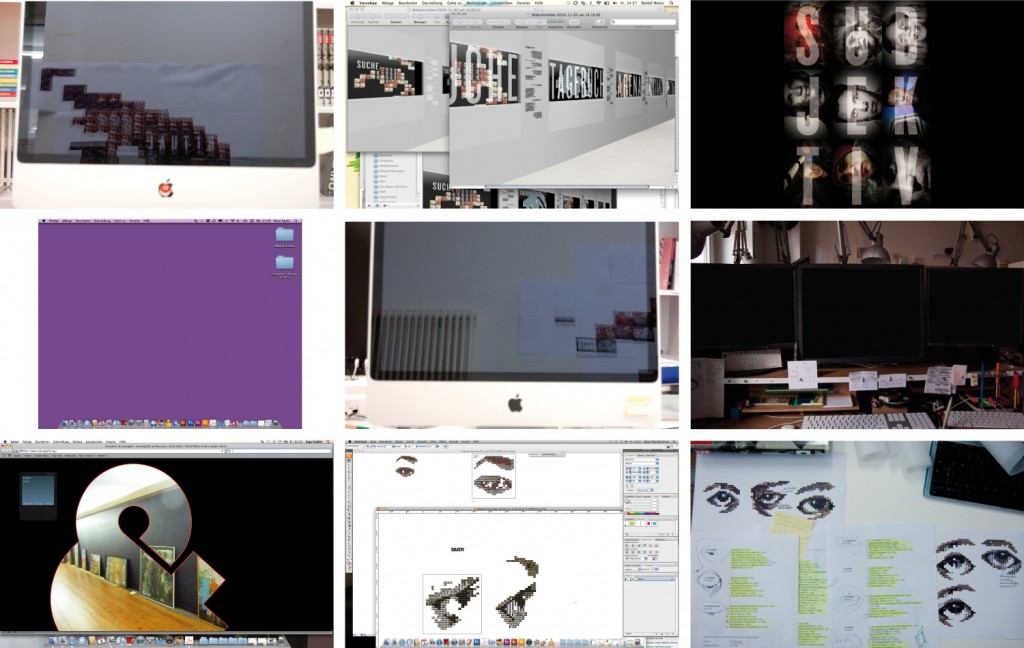

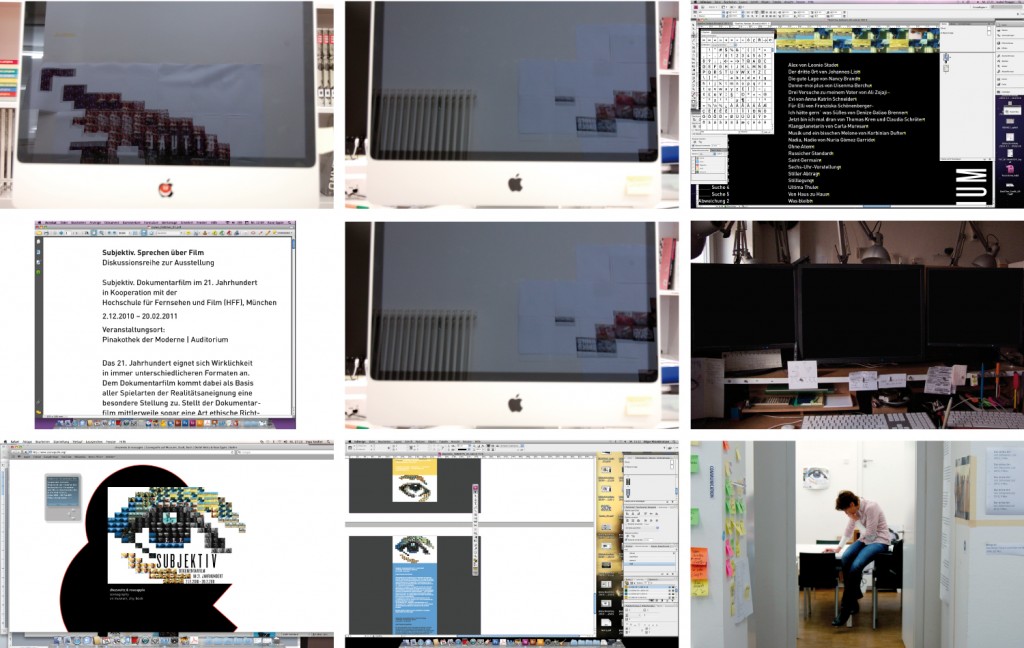

While we were working on an exhibition on documentary film, a collaboration between the University of Television and Film and the Pinakothek der Moderne, both in Munich, we (the graphic designers that is) had the idea of documenting our work on the show as a kind of meta documentary. As there was no documentary filmmaker about to do this for us, we thought of different ways of portraying the scenographic process without holding a camera. In the end, we decided that the common link between the collaborators is the computer screen. The task to collect a screenshot every day of the different team players fell to Edgar, our intern at that time, and he did a fantastic job collecting and posting them daily on a temporary Tumblr.

Here is a shortened version of what we did from October 21 to December 1 in 2010. Enjoy.

© chezweitz & roseapple · Tumblr Images and photos of opening: Edgar Khandzratyan

Writing About Exhibitions

From years of trying to find the right person to write adequately about our exhibition designs, I know how difficult it is to describe the design of a room with words. In my opinion, the writer needs to accomplish three things:

- clearly state what is there to be seen

- explain in easy words how it is done

- and then you might suggest the overall impression or athmosphere it creates – but be careful with! I personally hate to be told what I am supposed to experience

I drove a bunch of clearly talented writers nuts, because I felt they were always starting with point number three, didn´t understand what the clearly brilliant strokes were in number two and as for number one, that seemed to be the most difficult task of all. I hate to upset people, so I started writing them myself. Not because I was a better writer, but, at least, I knew what I wanted to be told.

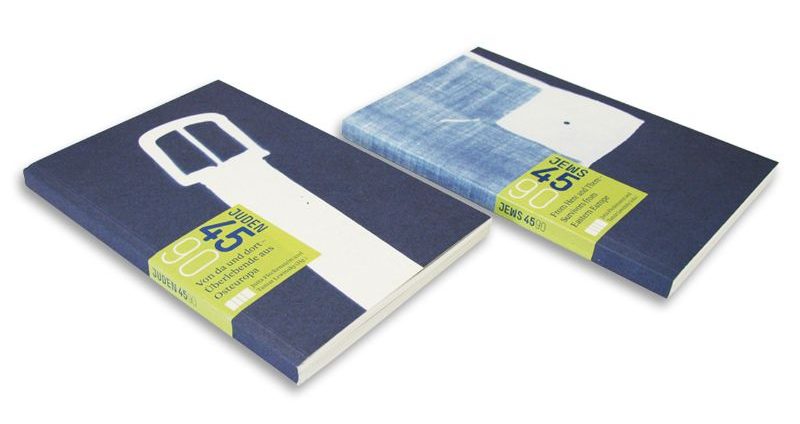

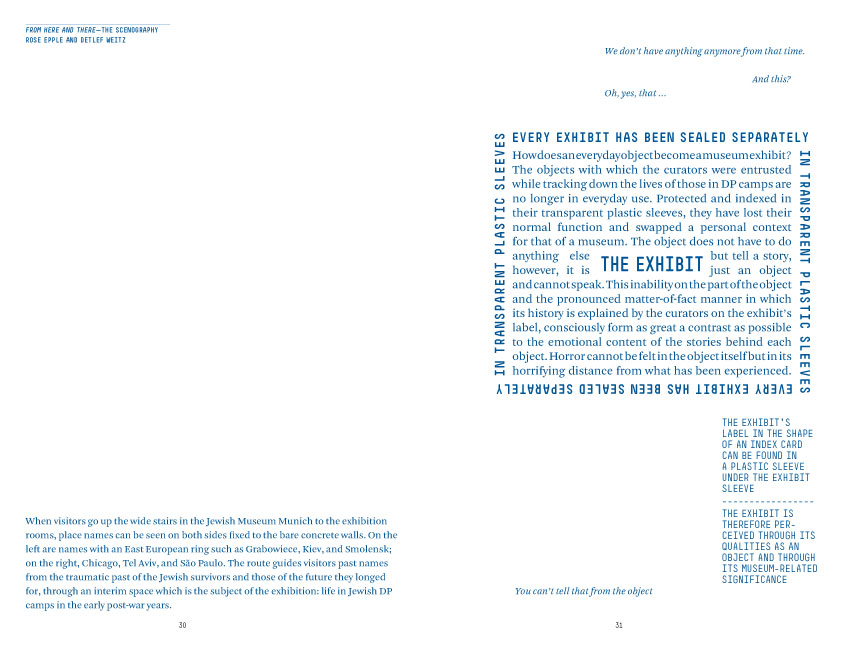

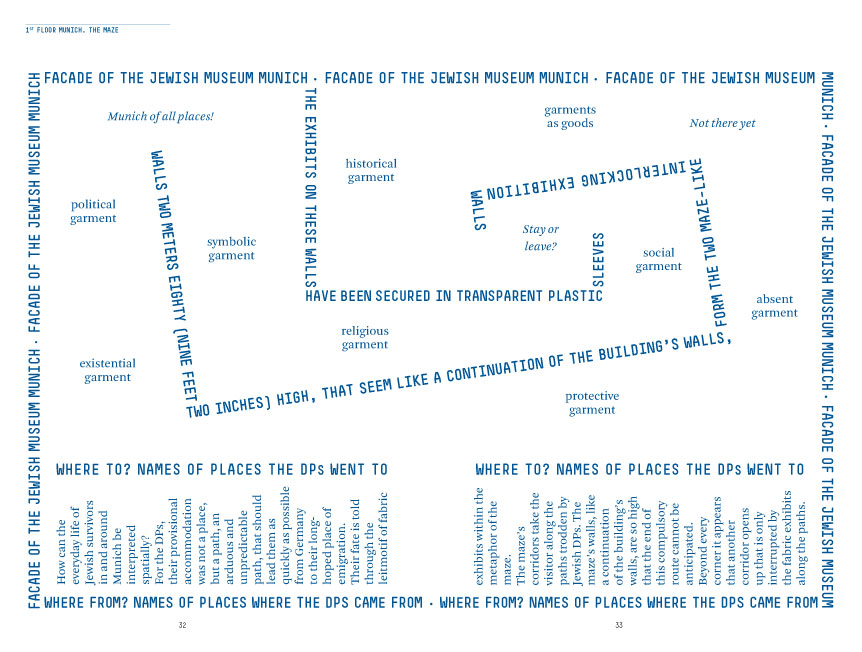

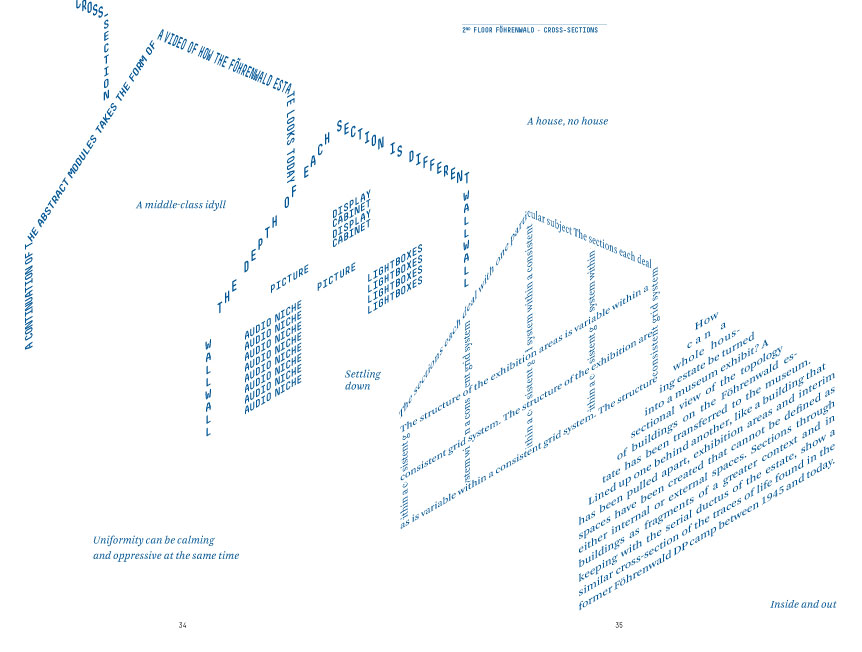

While writing a lenghty text about two Pasolini exhibitions of ours, I realized that indeed, words were quite a difficult and awkward tool compared to images to accomplish point one. This is why, when the next occasion arose and we were asked to contribute a text about the scenography of Jews 45/90, an exhibition in the Jewish Museum Munich for the catalogue, I set out to find a new form to “write” about our rooms.

And now I won´t attempt in words to describe this new form, but show you, simple as that:

The visual essay was first published in the catalogue accompanying an exhibition in the Jewish Museum Munich.

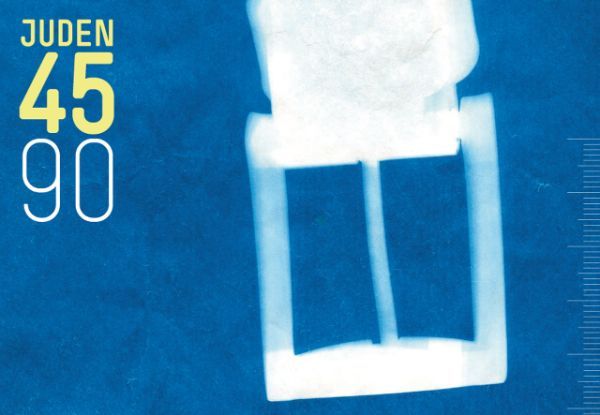

EXHIBITION

Jews 45/90. from here and there – survivors from eastern europe

Jewish Museum Munich, 30.11.11-17.6.12

Curators: Jutta Fleckenstein, Tamar Lewinsky

Visual identity, exhibition architecture and graphics, signage, printed matter, book design: chezweitz & roseapple

CATALOGUE

Jews 45/90. from here and there – survivors from Eastern Europe

Jewish Museum Munich

Hentrich & Hentrich Verlag, Berlin, 2011

136 pages, 25 ills. (German and English editions)

Editors: Jutta Fleckenstein, Tamar Lewinsky

Book design, illustrations and typesetting: chezweitz & roseapple

Showing Wilhelm Meister

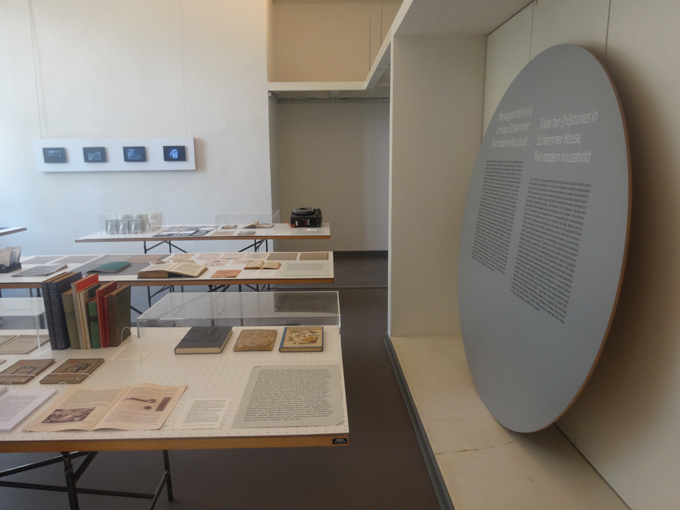

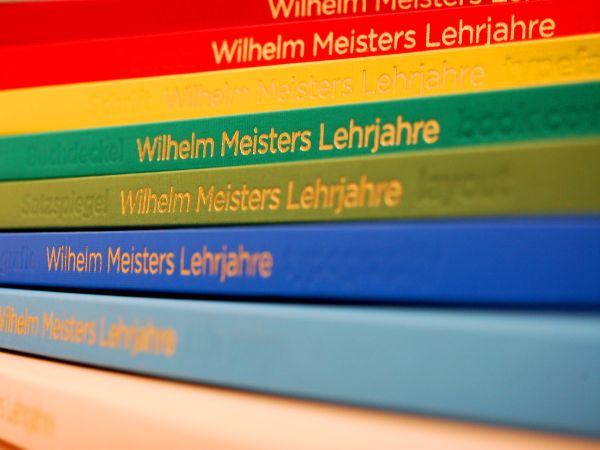

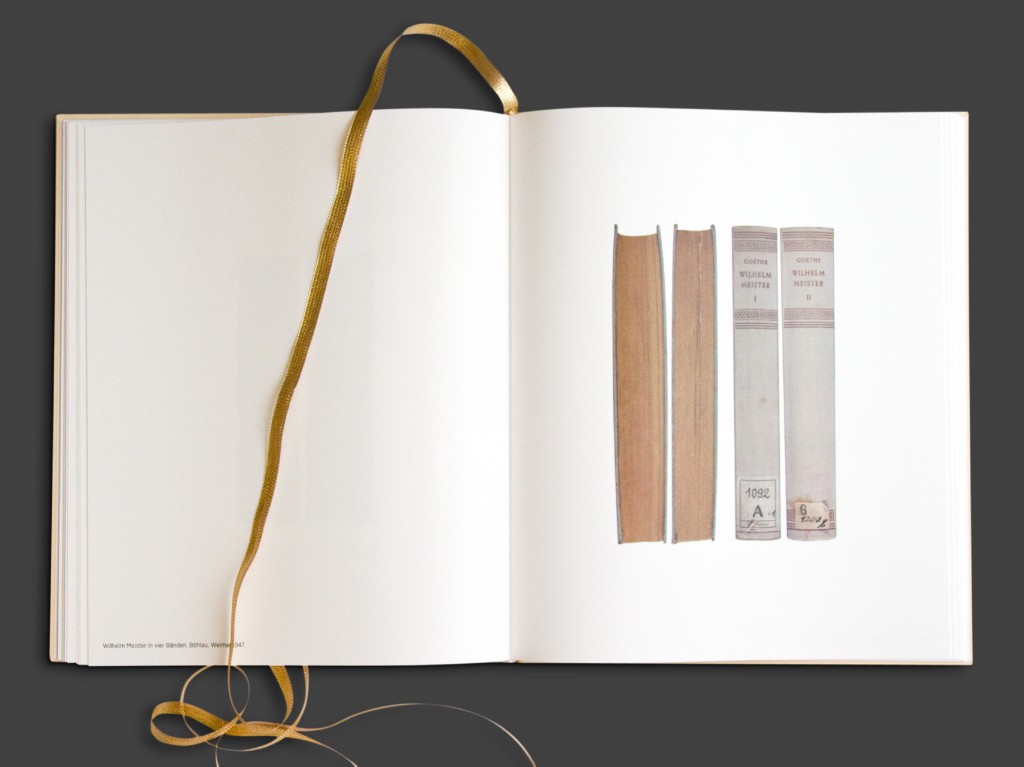

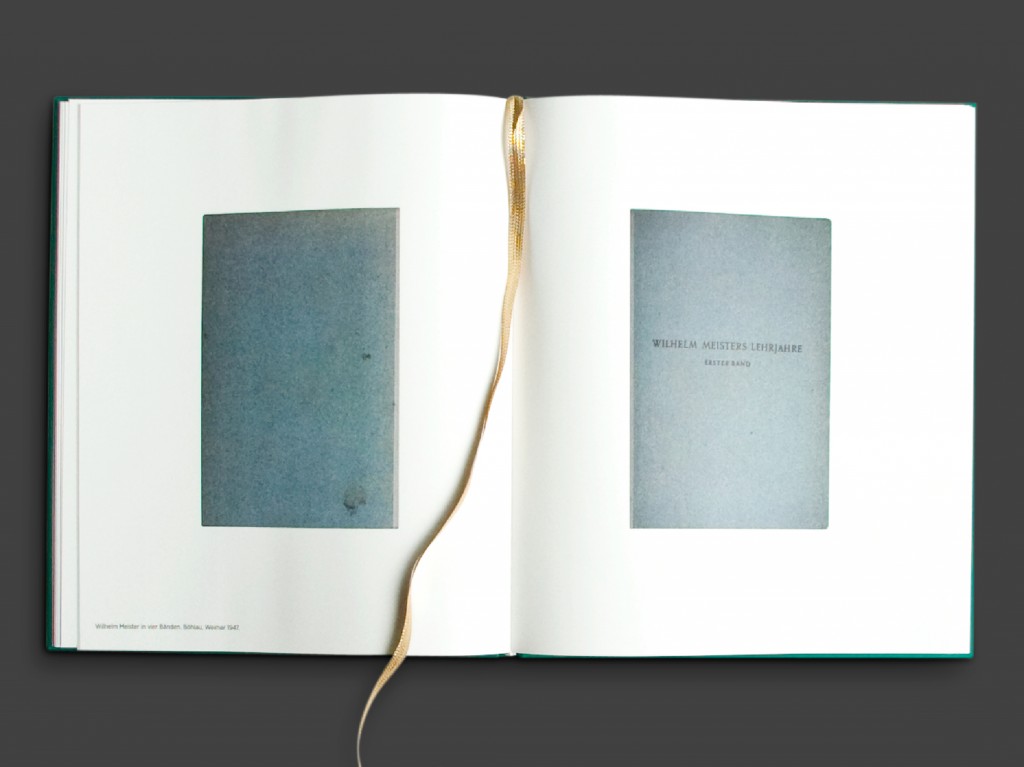

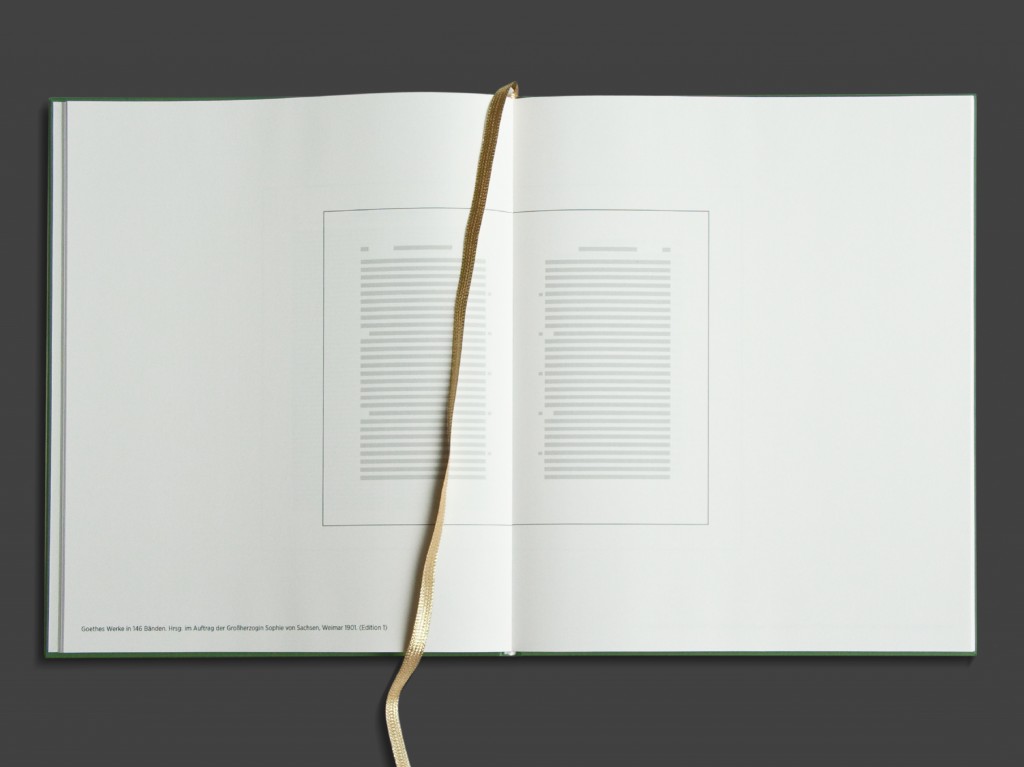

How to exhibit literature or more specifically Goethe’s famous coming-of-age novel ‘Wilhelm Meister’ ? That was the question put to seven renowned exhibition makers at a conference in Frankfurt in 2009. Being one of the few designers in an illustrous group of mainly literature experts, I suggested to show the book as an object. The form of the text obviously being something different than the text itself, I was curious what a comparable study of different editions of the books would reveal not only in terms of design and cultural history, but possibly also about the interpretation and literary status of the novel at different times. Feeling slightly guilty for still not having read the book, I was nonetheless delighted to be invited to test and present this approach in the ensuing group exhibiton at the Frankfurt Goethe-House.

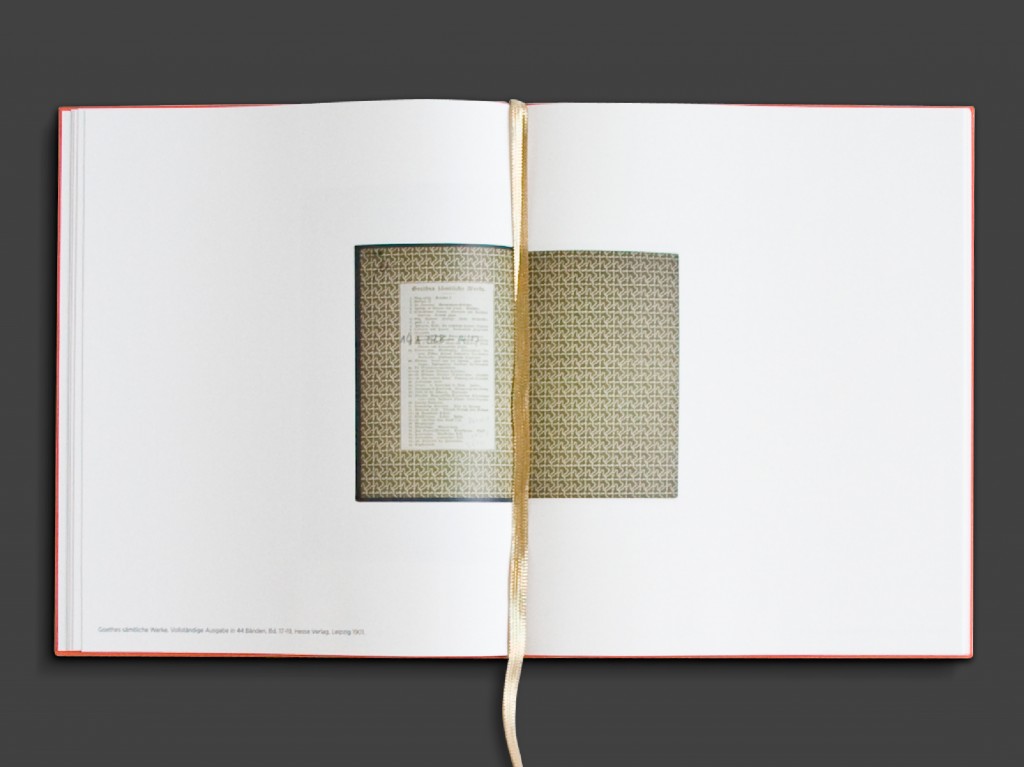

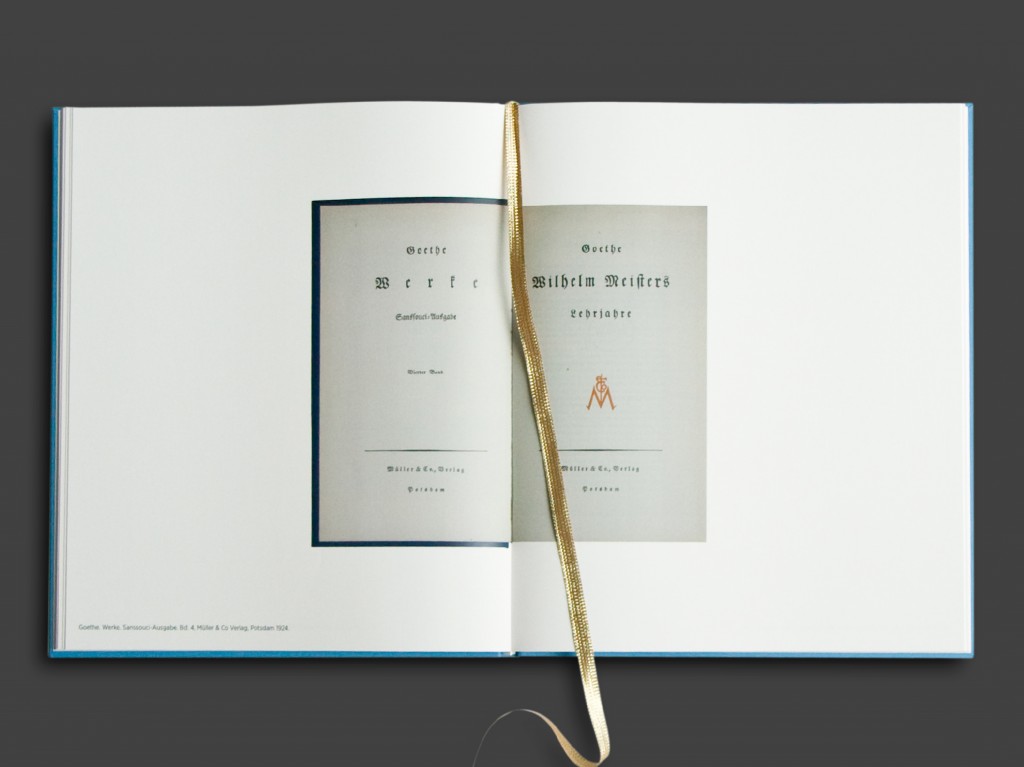

The Anna Amalia library in Weimar collects every new edition of Goethe’s works and posesses some of the original and very early editions and so was the ideal starting point for my research. I spent three delightful days in the very fine and welcoming library and examined 50 different editions of the novel, starting with the first edition from 1795 right up to a contemporary one of 2007. I weighed and measured, analyzed page layouts, identified lettertypes, compared title pages and endpapers. The findings were then organized in chronological order in nine exhibition books: The book of book covers, the book of typography, the book of layouts e.t.c..

Photo: Wolfgang Günzel

Curatorial concept, research and book design: Rose Epple

Installation: chezweitz & roseapple

Book photos: Isabel Prugger and Edgar Khandzratyan

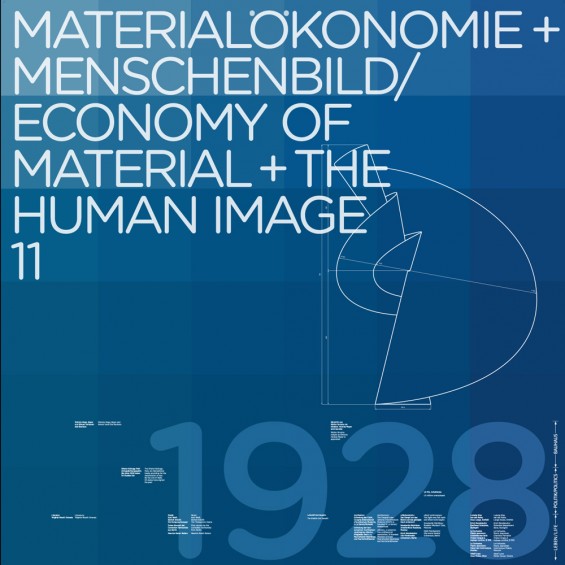

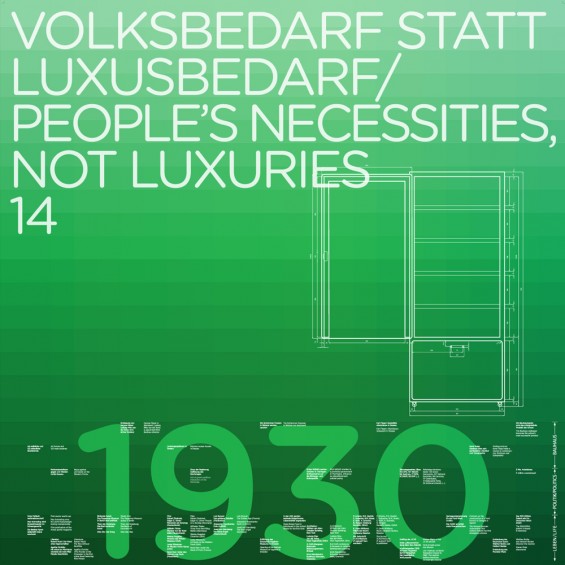

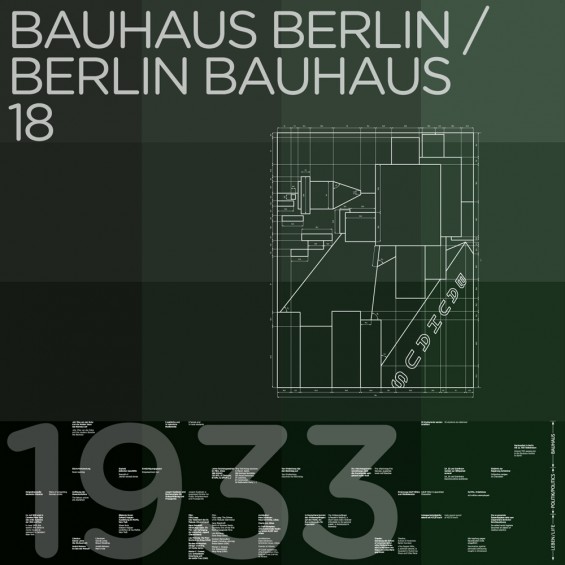

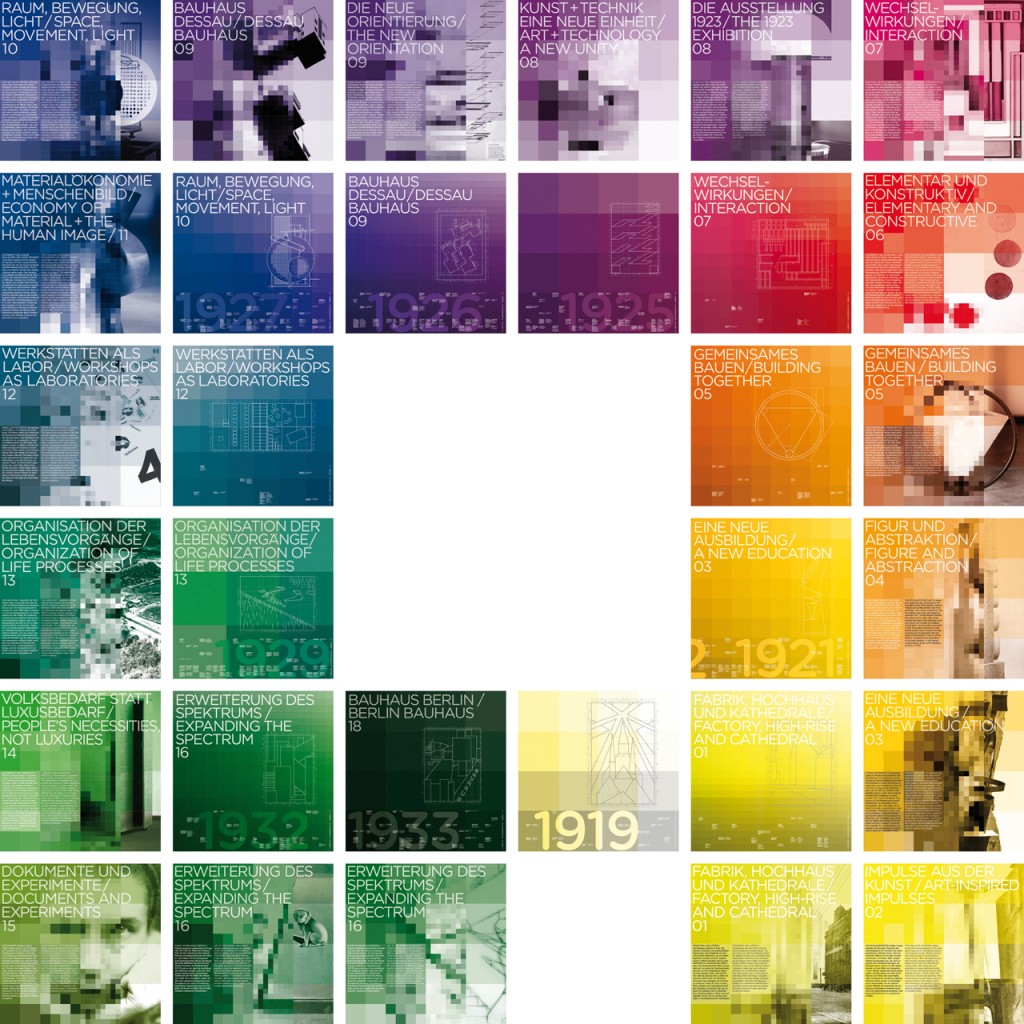

Navigating Bauhaus

My favourite graphic designer in the Bauhaus is László Moholy-Nagy. Graphic design was just one of many areas he was working in, and his layouts often seem a trifle inelegant and akward. But when it comes to translating ideas into graphic compositions, he is the boldest and the most inventive and engaging. He is trying to tell you something and he wants you to UNDERSTAND that something. That is because he could be your great-great-grandfather. He was born in 1895.

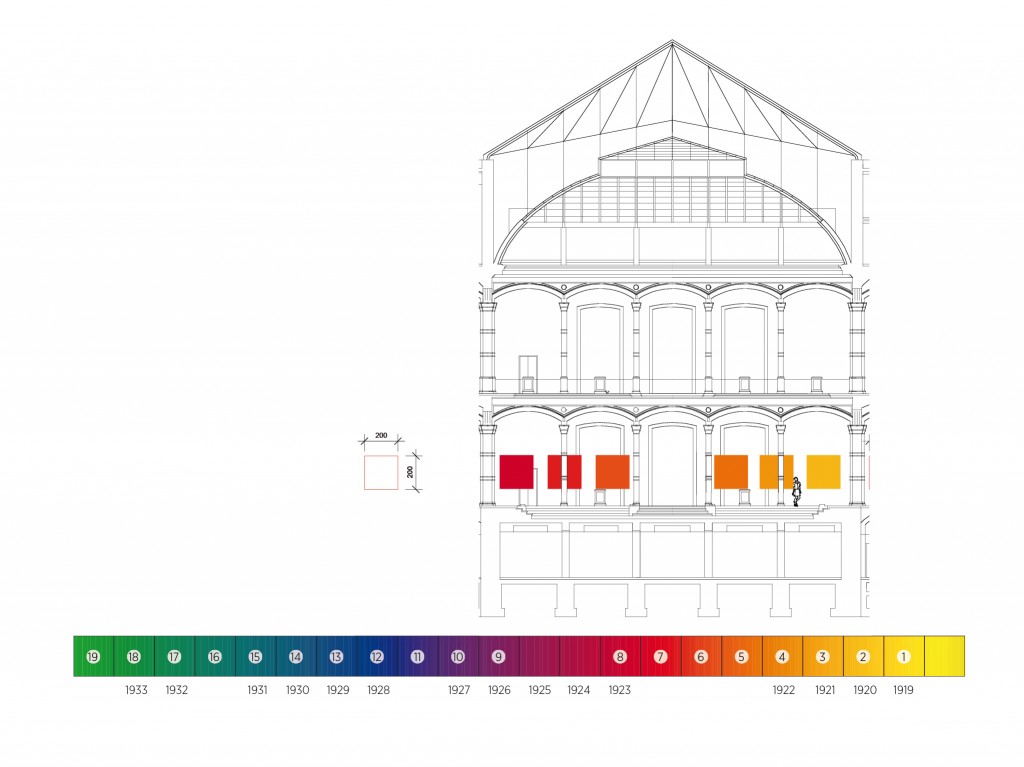

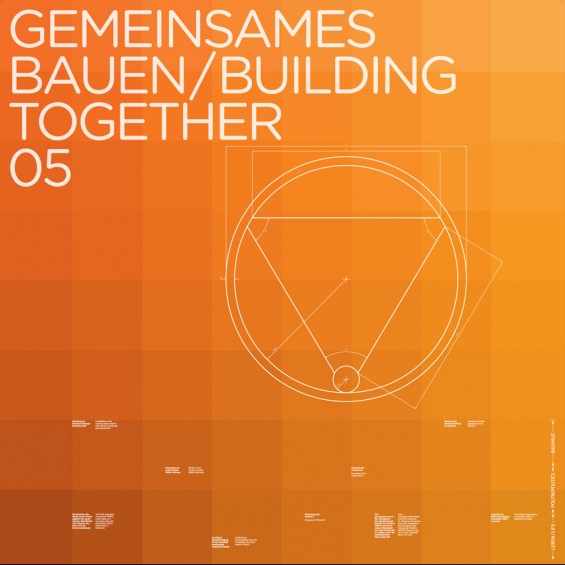

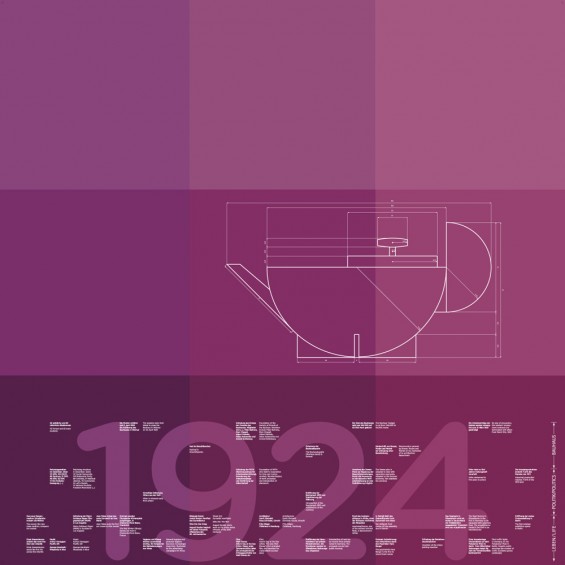

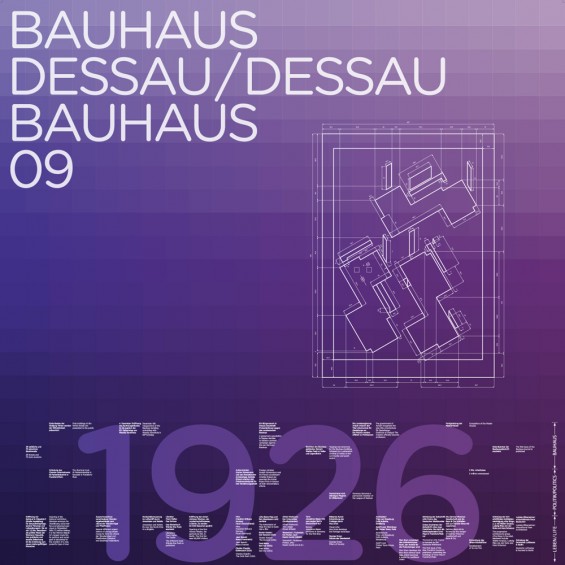

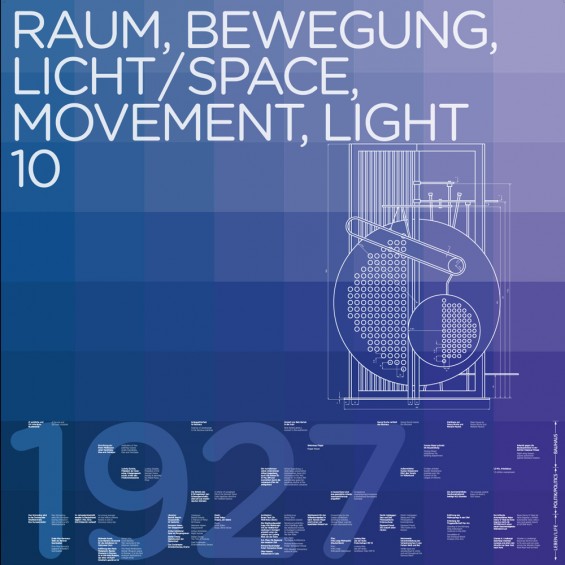

People often write about how contemporary and relevant the Bauhaus still is and how it’s cultural legacy can be found everywhere around us, which is probably correct, at least in the case of Germany. But while working on the graphic interface of the 90th anniversary Bauhaus Exhibition, I was more interested in pin-pointing the difference between now and 90 years ago.

Light-Space-Modulator by László Moholy-Nagy in the Modell Bauhaus Exhibition

One important difference I found, lies in the changed relationship between designer, content and audience. Whereas László Moholy-Nagy is one with his content and comes up real close to deliver his message into your face, the contemporary designer keeps a distance. He doesn´t shout, he doesn´t arrange his words for maximum impact, but to strict grammatical rules. He wants you to understand the underlying sentence structure first, the words second. He designs systems in which content is arranged, and then lets you draw your own conclusions.

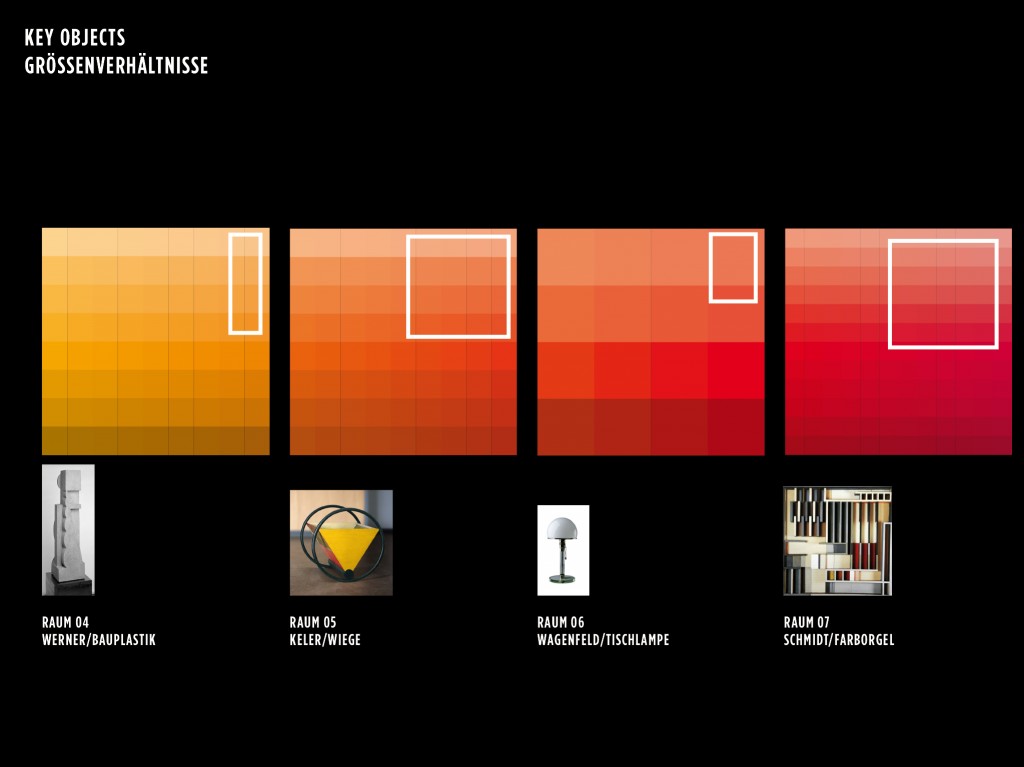

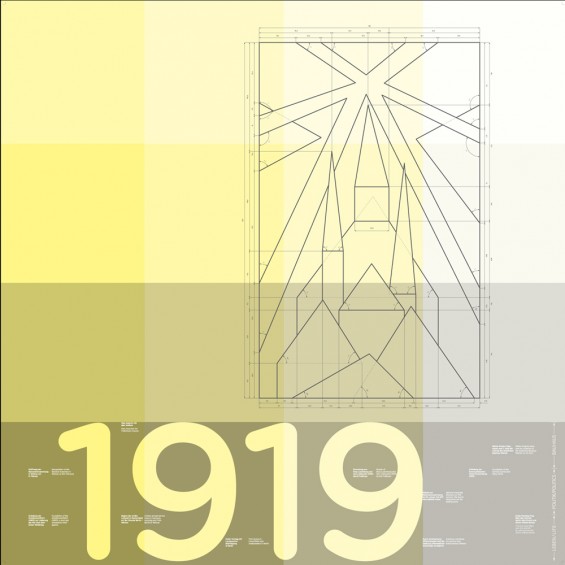

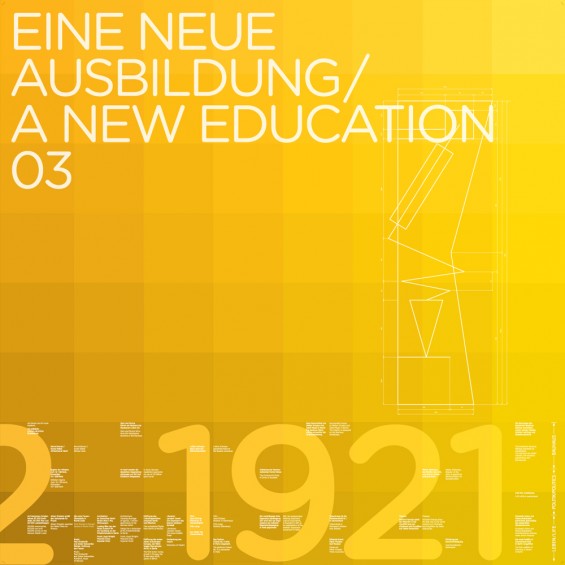

The contemporary designer not only keeps a distance to the content and the audience, but also to his own work and the idea of authorship. The thing that appeals to him in using systems is the element of chance. Graphic systems can be programmed to generate an aesthetic almost by themselves. They work like a bit like a Graphic-Meaning-Modulator, you feed some parameters into it and out comes a visual surprise. Here are our parameters for the 23 panels guiding the visitor from the inner Central Hall of the Martin-Gropius Bau into the outer exhibition ring.

- Every panel depicts a key object shown in the exhibition room the panel is guiding to, as a technical drawing.

- A chromatic circle runs over all 17 panels. The background colour of each panel is determined by its position in the great hall.

- All key objects occupy roughly the same size on the panel. The pixel ratio of the background is determined by the original size of the key object.

And now press start and see what happens:

Navigation System for the exhibition:

MODELL BAUHAUS | BAUHAUS. A CONCEPTUAL MODEL

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin, Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau, Klassik Stiftung Weimar

Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin, 22.7. – 4.10.09

exhibition design and graphics by chezweitz & roseapple.

Photos of the exhibition by Volker Kreidler

More about the exhibition here: Modell Bauhaus