Must every museum be interesting for kids? No, but if a museum aims to diversify its visitor groups – a declared goal of many museums – a good place to start is engaging with children. After all, the following urbanistic insight can also be applied to the museum realm:

“Children are a kind of indicator species, if we can build a successful city for children, we will have a successful city for everyone.”

Enrique Peñalosa, Former Mayor of Bogota, Colombia*

How do you make a museum accessible to kids? Ideally, by working with them: having conversations, observing them, developing ideas with them, building, testing, and improving prototypes with their help. This ‘Human Centred Approach’ has been an established technique in architecture and product design for a long time. In the German museum scene, however, it is taking longer to catch on.

While many museums offer guided tours and workshops for kids, they miss out on the chance to learn from their visitors. The experiences of the tour guides or workshop leads do not usually in turn influence curation and museum design. No wonder – offering a (specially funded) program is easier than questioning one’s own work.

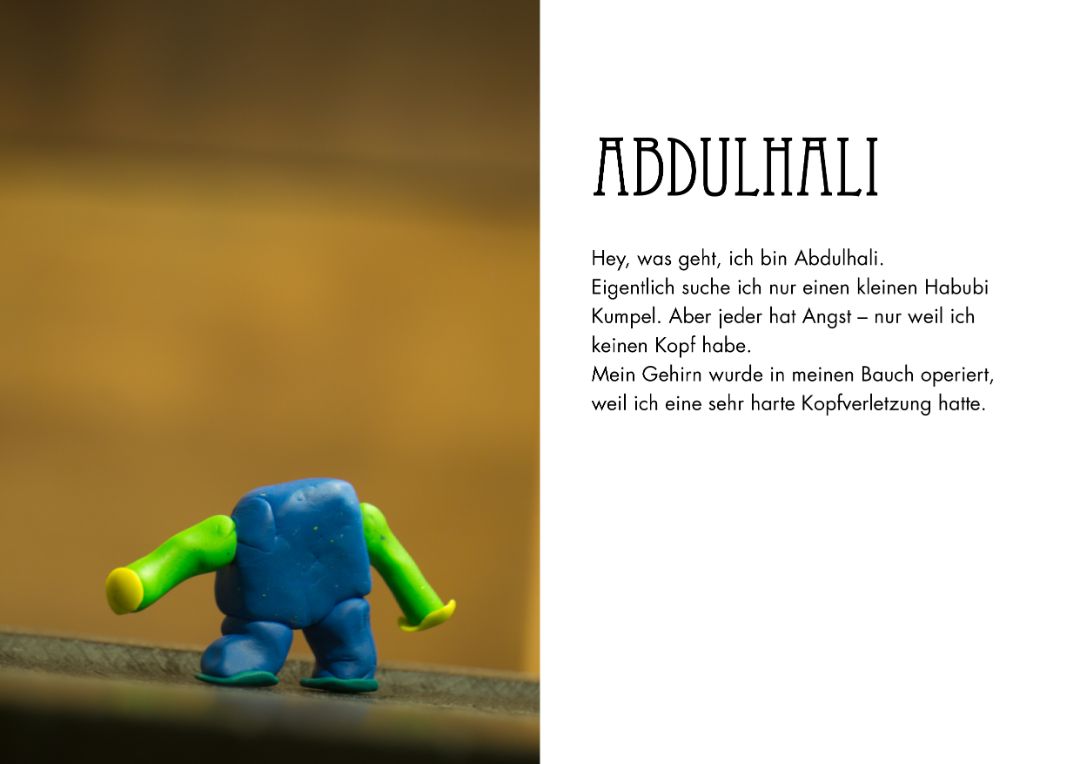

The Bröhan-Museum, Berlin’s museum for art nouveau, art deco and functionalism, on the other hand, was brave enough to ask: “How do children experience our museum, and what kind of museum do they dream of?”. In the summer of 2019, curator of outreach Nils Martin Müller started a Kinder Committee with the slogan “meddling strictly allowed”, which he asked me to lead.

I had the pleasure of working with twelve fantastic children from grades 5 and 6 and exploring the museum from their perspective, developing prototypes for a child accessible museum together. With the enthusiastic help of the teachers, the museum’s team and the cultural agents Berlin, the Kinder Committee met every Wednesday afternoon for a whole academic year.

A museum visit from the perspective of a child

Every change starts with stocktaking. First, the children explored the museum’s permanent exhibition as freely and peacefully as the museum rules allowed – no touching / no running / no loud noises. We asked them to photograph anything they saw that they would “talk about at home”.

So what did the children take pictures of? Of the 110 photos, there were many shots (25%) of large and spectacular pieces of furniture, such as Hector Guimard’s Water Lily Buffet, and extravagant glass containers (16%) in an illuminated display case that were “twinkling so prettily”, as one child put it.

What surprised us was the large proportion of “pictures of pictures” (16%). Among the paintings, graphics, posters, tapestries and reproduced photos, figurative motifs were particularly popular. The more text was on the pictures, the less interesting the children seemed to find them; the exhibition texts were ignored completely. Are two dimensional pictures a more familiar medium? Are the children searching for a narrative? Either way, pictures seem to be a medium that speaks to children.

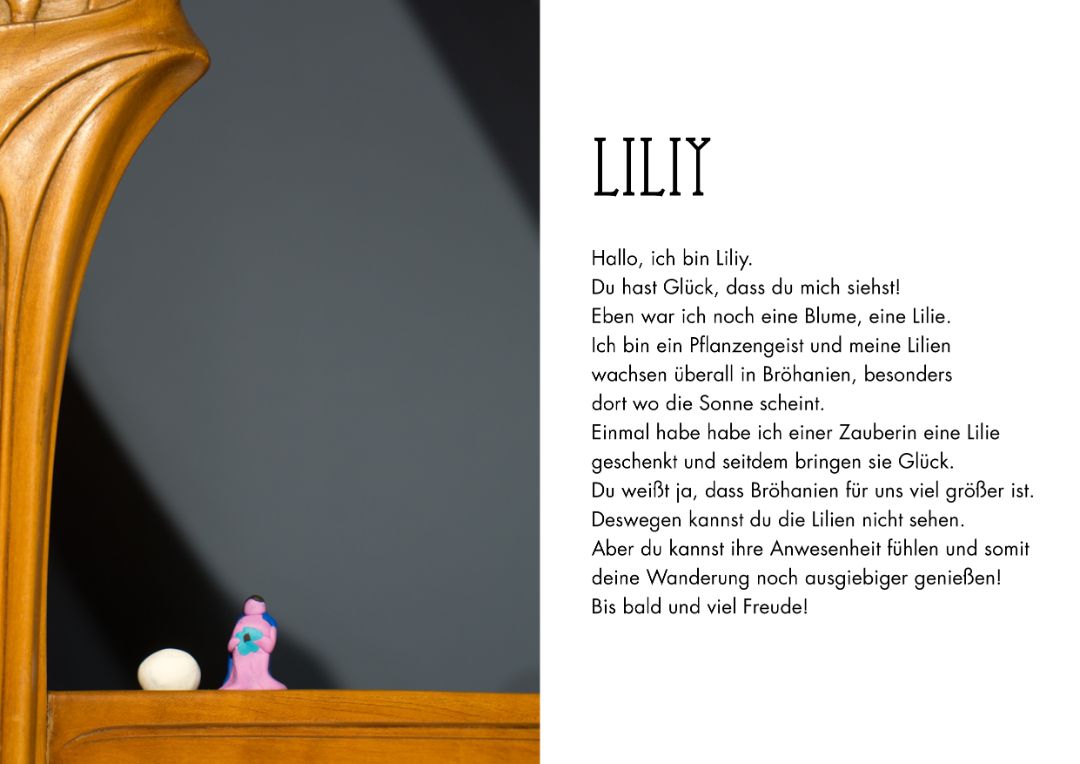

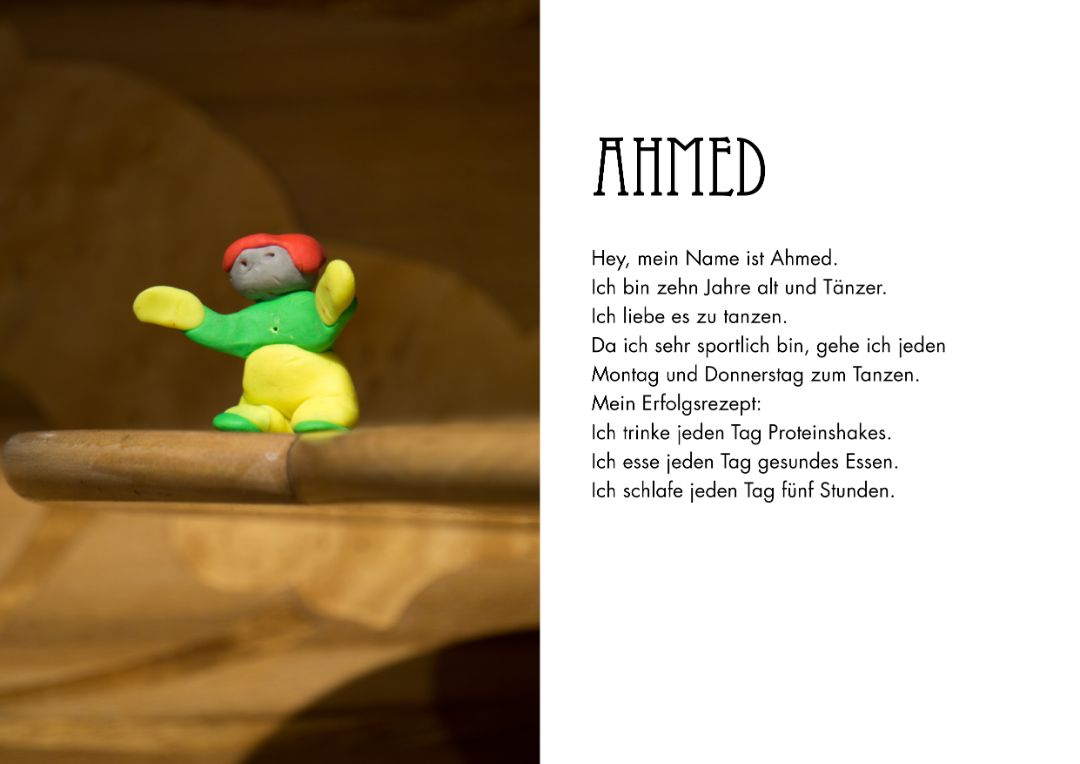

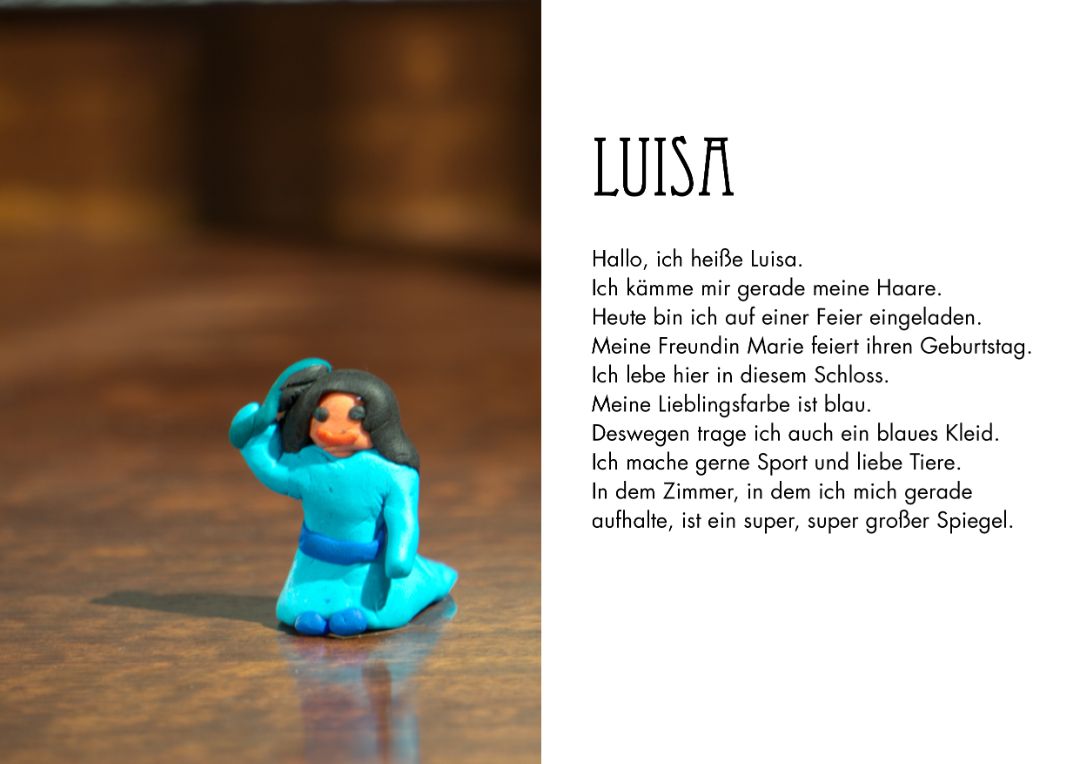

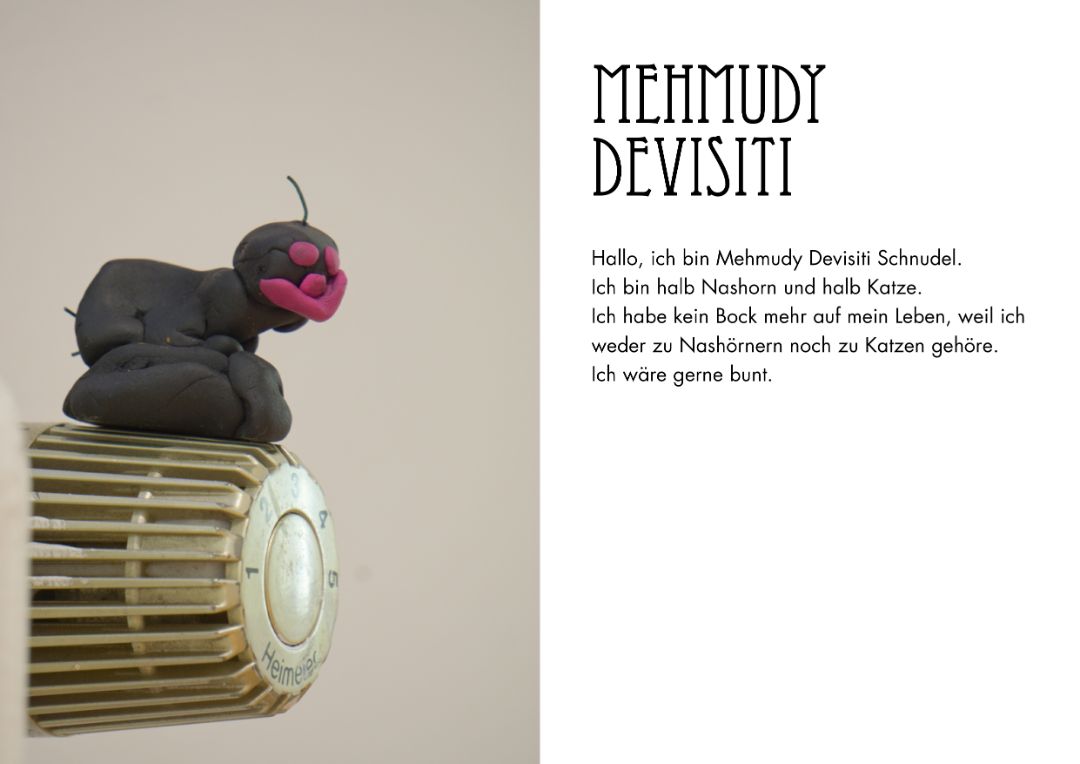

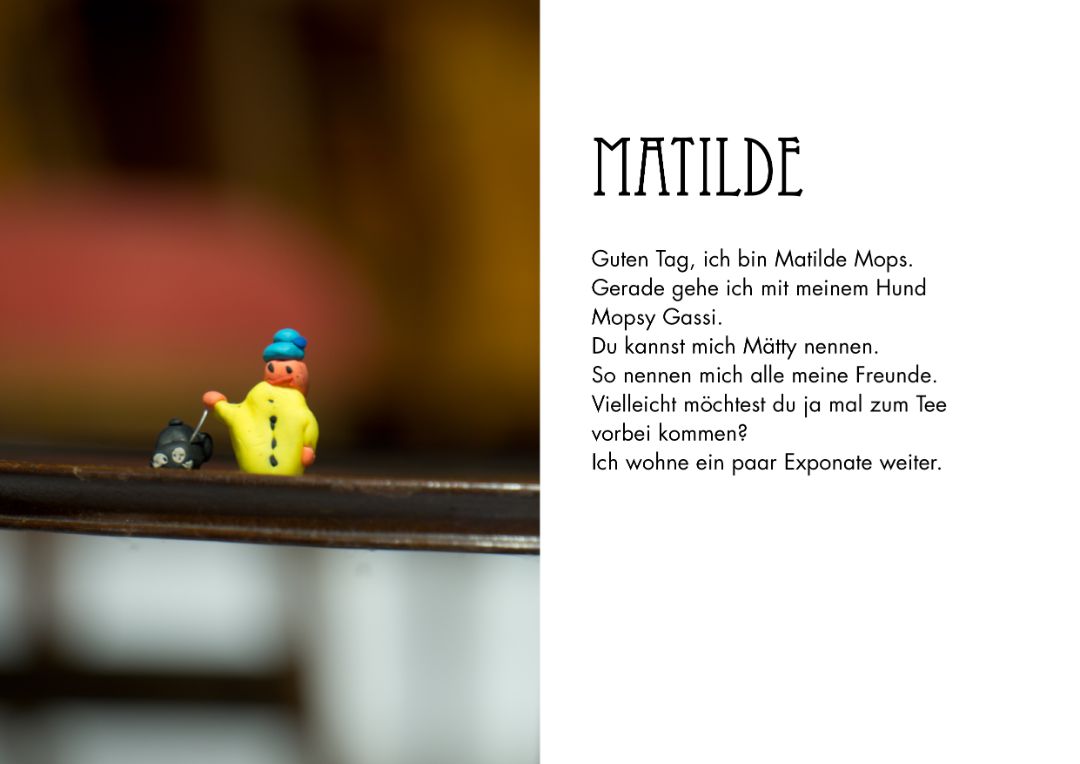

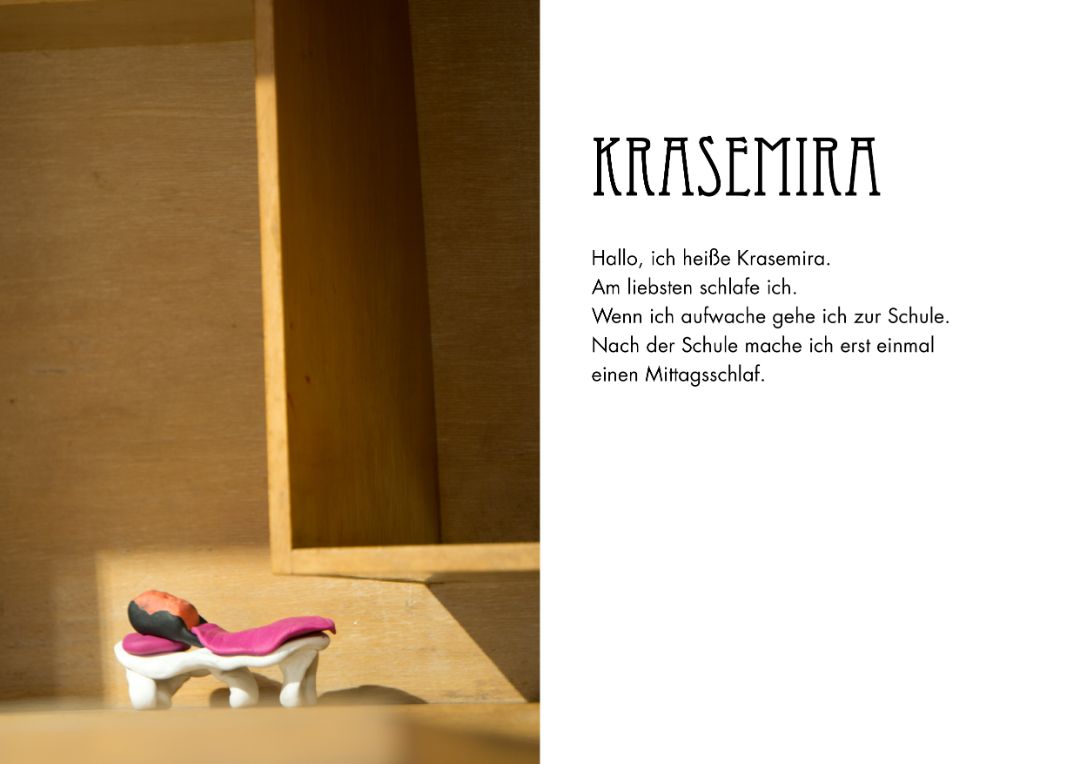

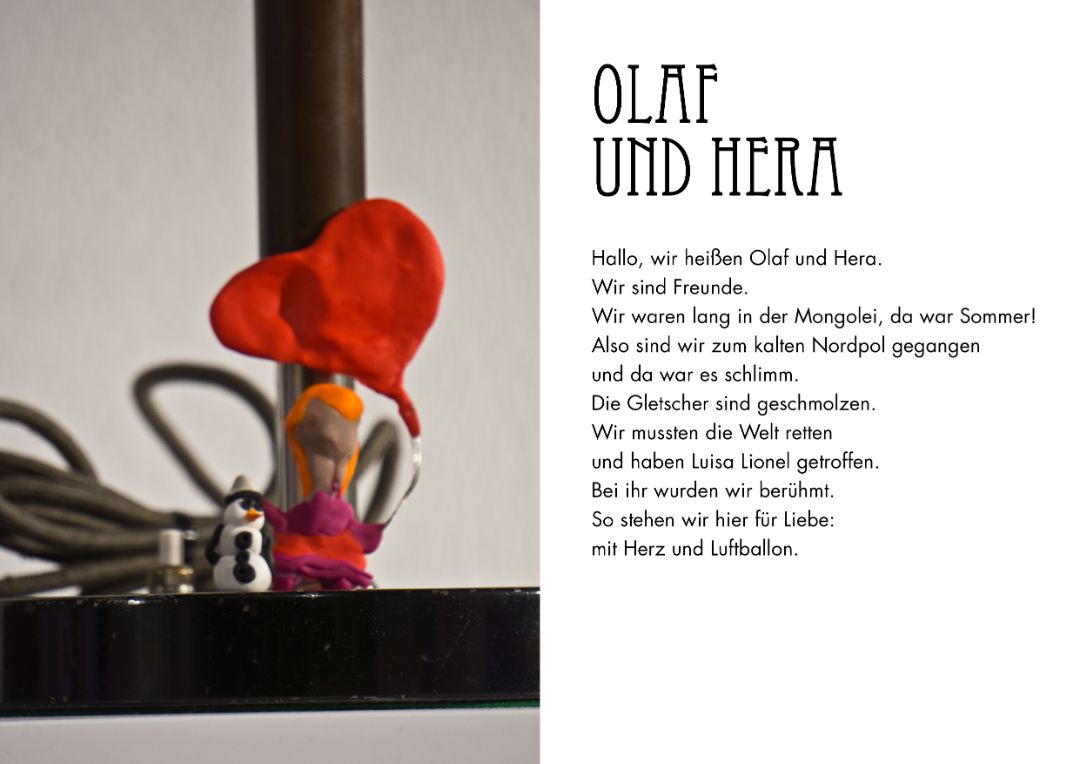

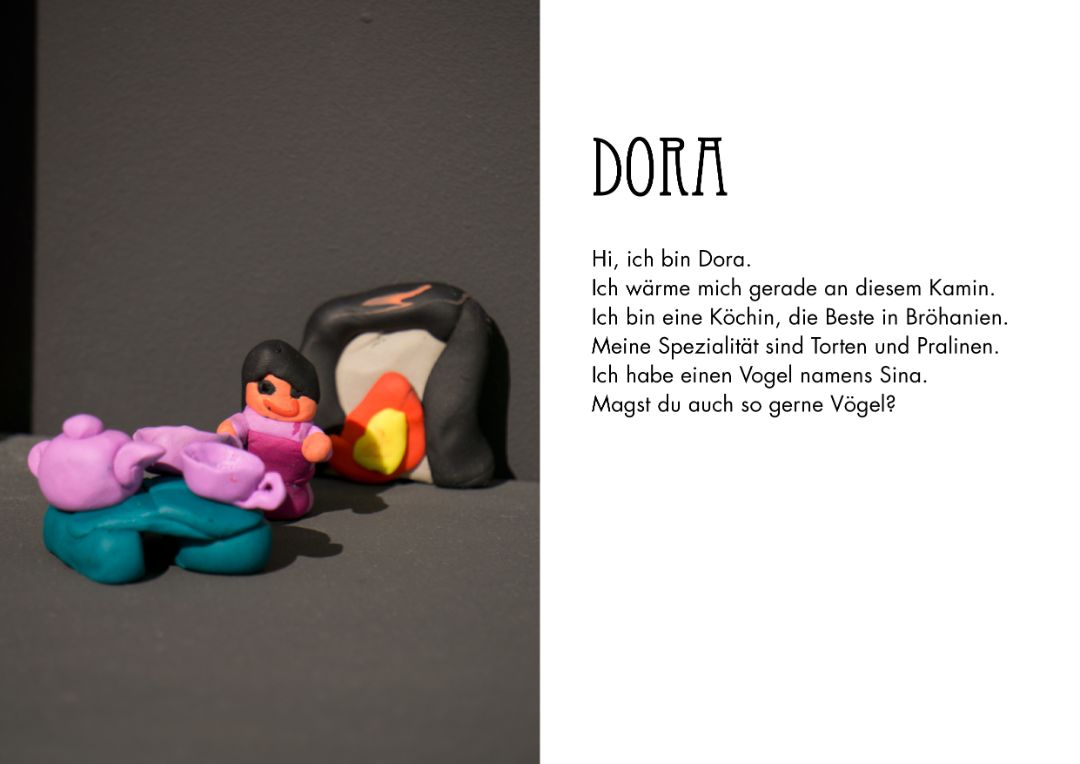

The children also photographed many things that experienced museum-goers might not even notice: the view out of the window or into the donation box. A useful hint: new visitors notice the periphery of the museum. Could we use it in a different way? Inspired by this observation, the children hid a miniature world in the museum: Welcome to Bröhania.

The mostly obstructed view into a storage room was especially intriguing. Perhaps sometimes exhibits could be hidden – discovering them for yourself is always more fun!

The items in the museum shop – although in display cases in the Bröhan-Museum and therefore not touchable – were documented just as eagerly as the exhibits. This supports my experience that museum shops can be a stimulating introduction to museums and their content. The Kinder Committee would probably have a lot of good product ideas for the museum shop.

On their photo safari, the children quickly identified the only interactive exhibit in the permanent exhibition – the big mirror at the end of the long corridor. The mirror unites two possible attractions during a museum visit: the possibility of social interaction (messing around together) and magically drawing you into the museum world. The potential for mirrors in the Bröhan-Museum has definitely not been exhausted yet.

The interesting thing was not just what the children found worthy of documenting, but also what they did not: Chairs? We have those at home, why are they in a museum? A good question – that ultimately asks about the concept of the collection and might need to be answered more clearly for many visitors.

Some display locations, like the highest display shelves or table cabinets, are wholly unreachable for children. Could aids be provided for this? A periscope or something similar would surely be fun.

Categorising the findings

We were very curious about how the kids would categorise their own pictures. While the curators sorted the exhibits by style (e.g. art nouveau) or designer (e.g. William Morris), the children divided them primarily into typologies (e.g. cabinet or shelf). In doing so, we found that the vocabulary for types of furniture was very limited – even the word ‘furniture’ was, in part, missing. Wouldn’t it be exciting to “take home” a few unusual words like ‘chiffonniere’ or ‘Sussex chair’? When you consider the enthusiasm with which kids learn difficult dinosaur names, the idea does not seem too far-fetched.

The second most common way of sorting pictures was by function (e.g. home life or tool). Functionality is a central concept in design, but the function of individual exhibits in the Bröhan-Museum is often hard to determine (not only) for kids. For example, a Morris bench was often called a shelf. Other functions might be antiquated – who still needs a ladies’ desk these days? So, an object’s function can also have a direct connection to its historical context. Perhaps there could be more clues about this in the exhibition – and in that context answer the question about the chair?

The subject matter of all pictorial artefacts was particularly dominant, regardless of material. The depiction of a swan on fabric was put in the category “people and animals”, and not “tapestries”. The fact that children really look at pictures and don’t just put them in a box according to style is a great chance! Could adult museum-goers learn from them to look at things directly, and not just compare them with prior knowledge? Mixed age “slow looking sessions” would surely be enriching for the adults.

On a side note, the children also seemed to enjoy forming meta categories like “scandalously pompous”. I would like to ask them to rename the rooms. I wonder what they would come up with for the collection “the social question”?

Children’s visions of the museum

Parallel to the exploration of the museum, the kids worked on their own shoe box museums. Every child chose their own theme and designed a museum according to their wishes. Together, it looks like the children have already made a checklist for an ‘inviting’ museum:

- A place where you can meet up

- A place where you play together

- A place where you produce something

- A place where you can try things

- A place where you can buy (take home?) things

- A place where you learn something about yourself

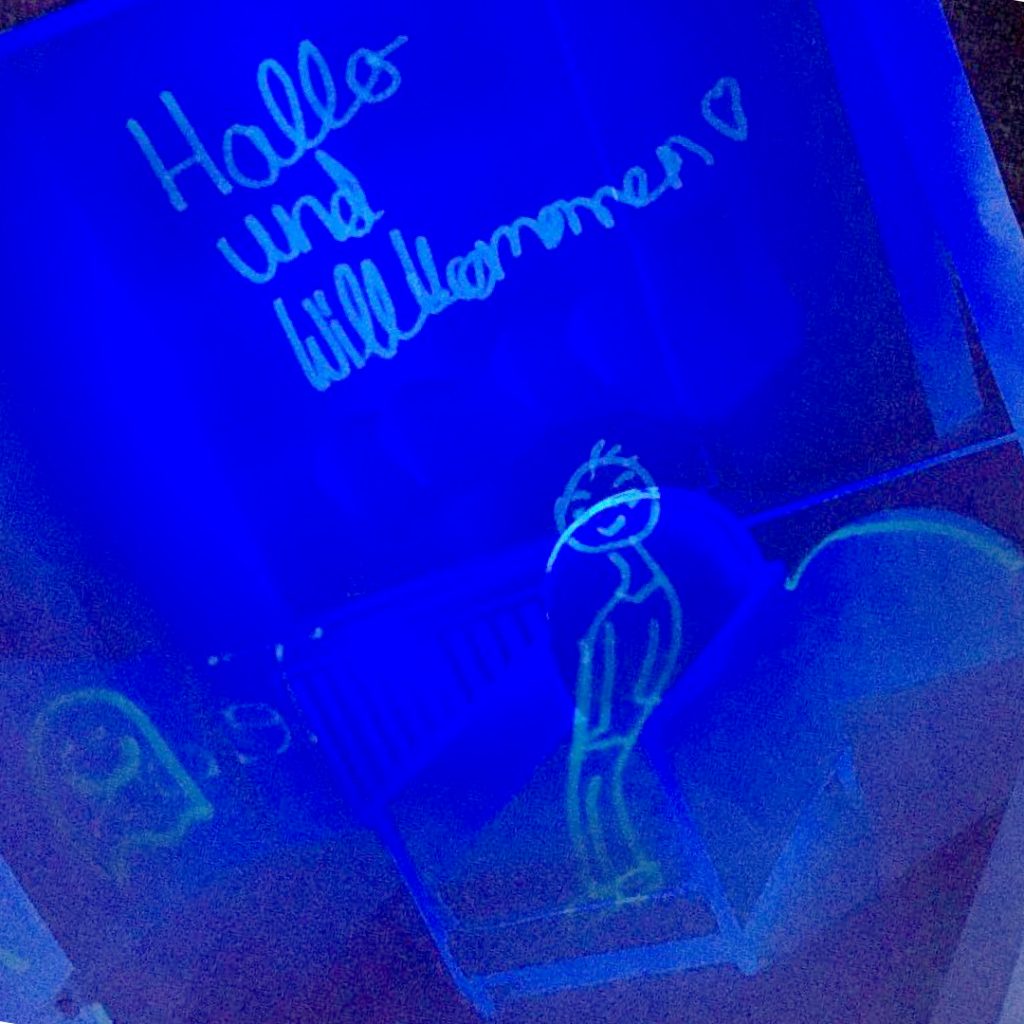

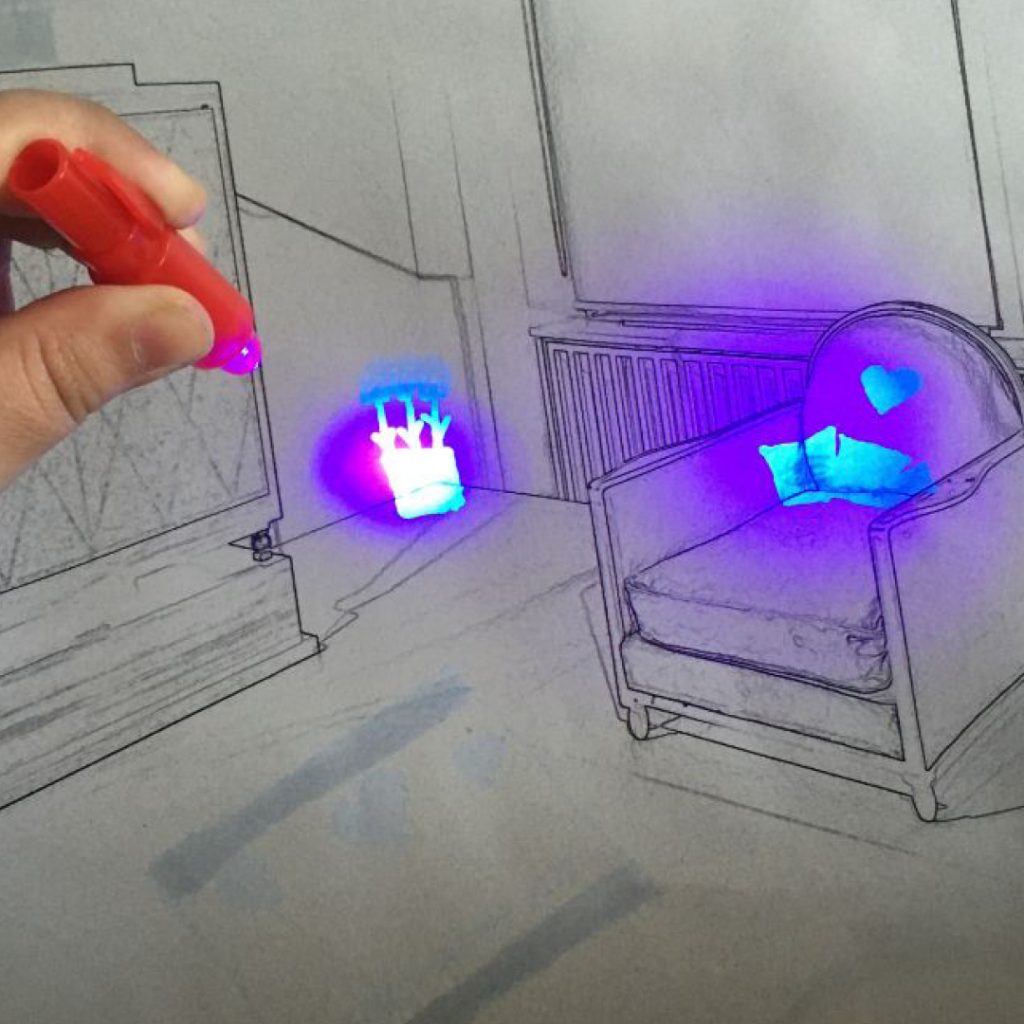

We reframed the children’s wishes as our challenges, and started by exploring the idea of the museum as a meeting place: “If the museum was a place where you met up and maybe even stayed overnight – what would happen there?” The children imagined what it would be like to sleep over in the museum and used glow-in-the-dark pens to illustrate the nightly activities. Their pictures are full of ideas and suggestions.

One drawing shows a doormat that reads “Welcome”. There’s no better way of saying it: new (and maybe shy) visitors want to feel welcome in the museum!

In another picture, Mr Bröhan himself is sitting in an armchair, greeting his guests. The fact that the man who lent his name to museum is not present within it, aside from a plaque at the entrance, bothers the kids. Using this mystical figure to create a welcoming atmosphere is a good idea.

In the above-mentioned picture, Mr Bröhan explains to his visitors that there are not only old (in the sense of “shabby”?) things, but also lots of wonderful new things in the museum. An interesting hint that some visitors might be put off by the age of the exhibits. The children, who are not likely to read the texts accompanying the exhibits voluntarily, generally have no concept of how old they actually are.

Most of the kids completely furnished the museum in their pictures – curtains, houseplants, paintings, ornaments, rugs, and pets. This makes sense – furniture usually has something to do with home life. The current exhibition lacks this angle, even though home life is something which everybody is familiar with and which could therefore be an accessible entry point for new visitors.

Some children were inspired by the Bröhan-Museum’s distinctive atmosphere to create fantastical parallel universes in its nocturnal rooms. Humans and ghosts living side-by-side and writing mysterious messages on the walls, skulls and crowns scattered around, doors leading to other worlds and magical books drawing you in. Children often have a sense of romanticism – think of Harry Potter – and the Bröhan-Museum’s magical aura is bursting with unused potential.

The next step was for the committee to consider how and what to play in the museum. But alas, the coronavirus stopped the Kinder Committee in its tracks. It would be wonderful to pick up where we left off next school year – there is so much left to do! Maybe together we can find a way to experience the museum, even with social distancing. In any case, we will be able to learn a lot from each other and have just as much fun!